Does A Serpent Effigy Drape Across This Northeastern Ridge?

Maybe I’m seeing things.

What I’m seeing is a large-scale effigy work on a ridgetop in Vermont. A Sea Serpent. Larger than I first imagined, upon my initial visit to the ridge. A return visit and additional study led me to understand the effigy encompassed the entire ridge and its surroundings, and also to discover that it was oddly representational at times — the stone of the ridge often worked to look like actual reptile skin in many places — with stones and boulders shaped, added and arranged to represent horns, fins, wings and feathers flowing off of the Great Horned Serpent.

This effigy idea, however, is evidently a radical one. My attempts to engage with archaeologists on this Serpent Effigy Ridge have so far been unsuccessful. One who did respond to my inquiries, Dr. Brad Lepper, of Ohio’s History Connection and a noted expert on Ohio’s Serpent Mound, simply cautioned me against Pareidolia, the tendency for our imagination to impose form on inanimate objects — seeing things like faces on cars or shapes in clouds. He didn’t have time to look at my evidence, however. Vermont’s State Archaeologist, Dr. Jess Robinson, has not responded to my emails.

Left to my own devices, I’ve begun investigating. As a trained journalist, an author and researcher, my approach to any mystery is to dig into it — do the research — and write about it, often learning through the writing. Though I don’t believe I’m seeing things — I’m sure that I am indeed seeing a serpent effigy on this ridge — and thus somewhat biased, I’ll do my best to present my case to you honestly, so you can decide for yourself.

This long-form piece presents that case by first covering the background context for the discovery, the deep history and culture of the area surrounding the ridge, as well as my own relevant background and recent investigations of New England’s stone workings. Next, I share with you my first discoveries of the effigy works at Raven Ridge, and reveal the first “wing fin” I found carved into the ridge itself. Then, through a series of photos and video stills, you’ll see more of the remarkable finds made. We finish with some questions and speculation about and on this remarkable Sea Serpent Effigy Ridge.

Raven Ridge is about seven miles from the shore of Lake Champlain in Northwestern Vermont. Lewis Creek creeps towards the lake to the North of the ridge, while Otter Creek rumbles into Champlain to the South. Northern New York and its Adirondacks line the western side of Lake Champlain, Vermont and its Green Mountains slope down on the east. The northern reach of the lake stretches over into Quebec, Canada.

The deep, glacier carved lake is said to possess a sinewy monster in its dark depths similar to “Nessie” of Loch Ness, this one given the nickname “Champ”.

Like Nessie and Loch Ness, Champ is a part of pop culture around the lake, appearing on souvenirs, T-Shirts and the like. Burlington, Vermont’s minor league baseball club is even nicknamed The Vermont Lake Monsters — Champ is their mascot.

Legends of a lake monster go back deep into history here, however, and predate Nessie sightings in Scotland, according to writer Robert Batholomew in The Untold Story of Champ.

Native Abenakis warned 17th century French explorers, hunters, and trappers, of monsters in Lake Champlain (or Bitawbagok — the Abenaki name for the lake), and cautioned them to be quiet in their canoes — lest they draw the monsters’ unwanted attentions.

They also used to tell stories of a mysterious “horned serpent”. The Abenaki had a name for an aquatic beast they called Gitaskogak, Gitaskog, or Peetaskog, the “great snake” that was believed to live in Bitawbagok, according to Batholomew in The Untold Story of Champ.

At native-languages.org Gitaskog (pronounced gee-tah-skog) is described as “a lake monster, an underwater horned serpent, common to the legends of most Algonquian tribes.” Gitaskog is said to “lurk in lakes and eat humans”. All of its names are variants on the meaning “great serpent” or “big serpent.”

Other ancient Abenaki legends are tied into the lake as well. Their oral traditions bind their people to this land back into the Ice Age.

Some legends tell of the creation of the rivers, mountains and Lake Champlain by the shaper — not creator, but shaper — Odzihozo, which seem to tell of the shaping of the land as The Champlain Sea receded and became Lake Champlain around 8200 BC.

After carving out the lake and its surrounding mountains and rivers, Odzihozo settled down and became a rock which now sits in the lake near Burlington, called “Rock Dunder” by Westerners.

This Lake was a Sea, originally. It’s the much smaller remnant of what was, at the end of the Ice Age, The Champlain Sea. Back then, most of Vermont’s future Queen City was under about 200 feet of salt water.

The Champlain Sea lapped at the shores of what would later become Vermont at what is now about 600 feet above sea level. Much of Burlington, at around 400 feet above sea level and lower, would have been below the waves — and a bit offshore.

Thanks to the glaciers of the Ice Age, this land was actually a lot lower back then, which is why there was a sea here in the first place. The weight of the then-receding Laurentian Ice Sheet had exerted enormous pressures on the land, pushing it down near or below sea level.

After the glaciers receded, the land slowly rose back up to where it is today, cutting off the northern route connecting the Champlain Sea to the Atlantic Ocean around 8200 BC and creating the smaller, freshwater Lake Champlain. Before that, The Champlain Sea was here for a few thousand years.

Archaeologists in Northwestern Vermont generally find Paleoindian remains at about 620 feet above sea level and higher in the suburbs and surroundings of Burlington, as Paleoindians lived near the shores of the Champlain Sea around the end of the Ice Age.

The Champlain Valley of Vermont, the area surrounding Raven Ridge, and the riverbanks of Otter and Lewis Creeks have been rich with finds of Native American habitation from across history, dating back over 11,000 years. An ancient ocher source and an ancient quarry are both nearby this effigy ridge. People have lived in this area for millennia.

With the entire range of years of pre-Colonial contact as a possible time frame, as I examine this effigy work the question of when it could have been built looms large. Stylistically, it doesn’t really fit in with other stone work I’ve been seeing around New England. The representational quality is very curious, and different from the more abstract natural constructs we see.

If it wasn’t for the unique aspects of the art at Raven Ridge, I might place its construction contemporary with the Hopewell or Adena of the Ohio Valley during the Early to Middle Woodland Period, circa 800 BC to 500 AD, who also constructed effigies, as well as geometric earthworks and mounds, or the later Fort Ancient culture there, to whom they now attribute the Ohio Serpent Mound.

There was cultural contact, at the very least through exchange networks — Native American artifacts originating in Ohio from this time period have been discovered in Vermont . At the Northern Boucher site, Adena-related artifacts were associated with the remains of a possible medicine keeper’s bag containing snake bones in red ochre. This evidence is circumstantial at best, but it suggests cultural ties, and could bolster an argument that work on the ridge might date to this time.

In fact, I’m one of a growing number of theorists suggesting the Native Americans of Northeastern North America actually worked in stone, constructing culturally significant Ceremonial Stone Landscapes, much as Native Americans are known to have done in the Ohio Valley, out West and in the Southwest. In the Northeast, these generally take the form of cairns and stone rows, symbolic or ritual stone constructs. Some are built incorporating abstract animal effigy forms, the shapes of the rocks suggesting snakes and turtles and the like.

Here’s an example of this sort of stone work from my ongoing research. CSL researcher Tim MacSweeney often illustrates photos with Eyes and Antlers, as you’ll find in both his facebook group Celebrating the Ceremonial Stone Landscapes of Turtle Island and his blog Waking Up On Turtle Island. It helps to illustrate the phenomenon in an interpretive way. He recently illustrated my photos of one of these potentially indigenous stone rows in Massachusetts which I’d shared shared in a facebook group.

Some evidence suggests these stone wall and cairn constructs were built above underground water sources, places where the earth “sang” with the sound of water rushing underground, the stone rows above mirroring the flows below.

I’ve also been exploring Stone Chambers in New England. Thus far I’m struck by how much they don’t have in common. Though identified as colonial constructs by much of mainstream archaeology, my favored theory — having now experienced a few in the field — is that many of these stone chambers have earlier, Native American provenances than currently allowed for, and were then often re-purposed by later European Colonists.

Some Stone Chambers are indeed Colonial, however, and some even post-colonial. As an example, upon investigation, one mysterious Tunnel Chamber — in a secret location near Bolton, Vermont — appears to have been a not-so-mysterious Stone Culvert, once under a road washed out by Vermont’s Great Flood of 1927 (though there are other, more mysterious stones near that location — a subject for another time…).

None of the Stone Chambers, Walls or Cairns I’d seen prepared me for what I‘ve discovered at Raven Ridge, however. The scale of the effigy work at the ridge is immense. As I’ve mentioned, the art is more representational than the abstract stoneworks I’ve grown used to seeing. It’s difficult to place its time of construction. And so far as I know, no one else has seen this, at least, not yet. Thus far, I’m the only one reporting on this effigy. The one thing I’ve not found in any of my research is another reference to this find.

Everything about this Serpent Effigy discovery at Raven Ridge has been unexpected. I didn’t venture to the ridge in search of anything except a nice hike, and maybe a look at a natural feature known as an anticline folks call “The Oven”, a natural folding of rock some say resembles an old open-hearth stone oven, or pizza oven. The suggestion to visit came the same morning I first went out there, after I’d asked friends on facebook where I could go that day, a spontaneous thing.

Driving from Burlington, I headed south on that early Sunday morning. Raven Ridge sits on the boundary between Chittenden and Addison counties and on the border of three towns, Charlotte, Hinesburg and Monkton, Vermont. It’s a home to bobcats, porcupines, and — naturally — ravens. It’s protected as a nature reserve by The Nature Conservancy (Nature.org), and open to the public for hiking — details are on their website.

In relating the natural history of the ridge on their site, they go back even further than The Champlain Sea. Prior to the Sea, most of our current state was entirely covered by the glacial Lake Vermont. They conjure an image of the ridge as an island:

The continental ice sheet started melting roughly 15,000 years ago, deepening glacial Lake Vermont, and turning 800-foot-high Raven Ridge into a refugia — an island of dry land encircled by icy waters. Today, Raven Ridge is still a refuge, a craggy green oasis perched above a sea of civilization in the Champlain Valley (nature.org).

They also mention in their description how former landowner Raven Davis loved, “the ledges. Beautiful, overgrown with mosses, rising like the walls of an old city…” .

A suggestion of the ridge’s secret, in some sense hiding in plain sight, comes through here. Perhaps they couldn’t help but sense there was more to this place? Maybe someone caught a whiff of the aquatic context? Or perhaps sensed a lingering aura of repeated rituals?

Even so, they couldn’t, or wouldn’t allow themselves to take the leap and see what seems to be laid out all over.

In the days of The Champlain Sea, this ridge would still have been an island near shore, or the promontory of a peninsula. Given the aquatic nature of the effigy themes here, and the fact the most prominent begin at or about the 600 foot mark, I believe this context suggests the effigy work could date that far back, back to the days of The Champlain Sea or even earlier Lake Vermont. This, however, runs up against conventional wisdom in many ways.

Conventional wisdom isn’t all it used to be, however. Though it was long assumed that ancient hunter-gatherers, as the early inhabitants of Vermont are theorized to be, did not construct permanent places — homes, cities, nor anything akin to later temples or even standing stones — those theories have been challenged by the discovery of ancient Gobekli Tepe on a ridge top in Turkey, built over there presumably by hunter-gatherers, as the Champlain Sea lapped up against this ridge here, on the other side of the globe.

This is not to suggest any connection between these two ancient places. However, it does occur to me that like many ancient cultures, including some of those in Anatolia, the Abenaki do have an oral tradition of Seven Half-humans, their Padongiak or Padôgiyik — Thunder Brothers — coming up from the water, in their case, Lake Champlain, in the earliest of days.

Those fierce half-bird warriors were said to shoot their enemies with lightning. In some legends, Thunders had wings they could take off and put back on which allowed them to fly, and they are sometimes described as white beings with long golden hair.

Make of all that what you will. Some rather intense lines of speculation could be developed here. We are more concerned with Serpents than Birds, for the moment, however. Though given the prevalence of both symbols evident in pre-history, we might wonder if two different ancient groups weren’t vying for the attentions of our ancestors, those who followed The Serpent and those who followed The Thunderbird. At any rate, the effigy builders at Raven Ridge certainly seemed to follow the Great Horned Serpent.

COVID-19 has changed the way we do many things — including hiking. I hike with my mask at hand and socially distance myself from other hikers, especially if they are not masked. Raven Ridge is a very public hiking space, and I needed to step out of the way of families both masked and unmasked at a couple of points during my first morning’s visit.

I might not have noticed the Serpent on the ridgeline that morning had I not had to step aside and wait, although I had seen a couple of possible effigy stones before noticing the ridge. That said? I’m not entirely sure of the first effigy I spotted, but the second I still believe to be some sort of fish. There is intricate carving across much of its surface, it’s not the erosive work of water and glaciers.

Carving? Sculpted rock? How would I know? In one of those odd ways life prepares you for later experiences, I have a friend and former roommate who was a stone sculptor. Thanks to her, I have a better-than-average appreciation for what sculpted Vermont stone looks like, having often seen her work and seen her at work. I also spent two years working myself through college as a mason tender, laboring for those piling up courses of brick and industrial block, so my appreciation for big-block construction techniques comes from a practical background as well.

It’s surprising how life sometimes prepares us for what lies ahead. My past and my research into Native American stone work certainly prepared me for some of what I first found at Raven Ridge. Happy accident then presented me with so much more.

After visiting The Oven, I wandered up the ridge trail and noticed stones underfoot. This got my attention.

Eight-hundred feet above sea level, on a ridge top, I did not believe this was an old colonial road. I thought instead of Native American paving, a way of leveling uneven space using larger-sized gravel and dirt, and realized I should be on the lookout for other signs of Native American work.

That’s when I spotted the Narwhal.

Well, I thought it could be a narwhal. It seemed deliberately shaped to be something. Its greatest importance lies in the way it shifted my perspective, not in how it still conjures up the B-52’s “Rock Lobster” in my head — “There goes a Narwhal…” Because I realized right then — for the… narhwal… to be anything, there had to be something else around.

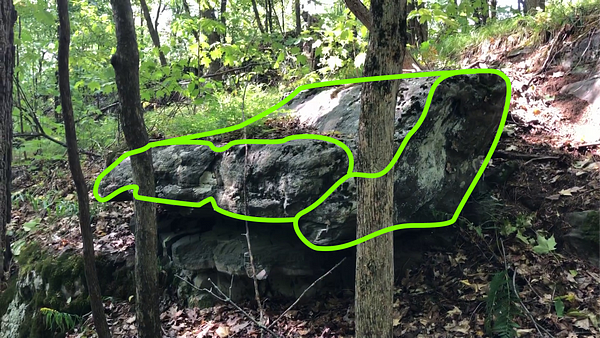

I spotted the Fish up ahead, in the trees on the left. It looked a bit like some sort of prehistoric fish or porpoise. This is not normal, naturally occurring stone work, as you can see in the large picture of it above. Below is a picture of the possible Fish Effigy Stone with my subjective outline next to it to show you what I’m talking about.

Walking on, I thought there could be more effigy stones on the ridge, and kept my eyes open for them. I found myself up near the top of the ridge looking at a sort of rounded, but also sort of busted-up prominence of bedrock.

Seeing the rounded edges and given the aquatic stone life I’d just seen — and the fact this thing in front of me was so big — I wondered if it was… maybe… supposed to be a whale?

A whale?

And that’s when I needed to step aside for a two-family group hiking through.

It put me closer to and more in front of the huge bedrock rising up out of the ridge. Was it a whale?

As the other hikers moved ahead, I moved up to look even closer.

A minute or two later, I needed to get closer to the ridge yet still, to socially distance, as apparently a few stragglers from the group came up from behind me. Though I’d never admit it, I may have been shooting video of the ridge just to avoid the parents and kids as they walked and talked past me.

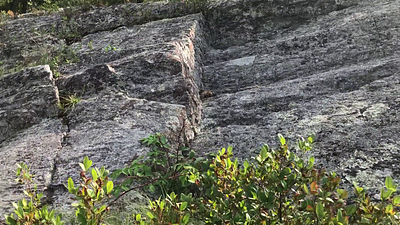

But what I was seeing as I shot footage of the ridge up close was changing my aversion techniques into awesome curiosity. The stone appeared worked to resemble reptile skin, and stones appeared added to the sides… and the ridge itself seemed to be cut and sculpted to appear as though fins were sweeping off from it.

Our minds have trouble accepting such things, however, and I might have just shaken my head and moved on, but the entire crew which had passed me now seemed to be stopped on the scenic outlook just ahead of me , by the sound of it. It also sounded like one of the little ones might be having a little trouble with the height. So I lingered on, looking at the ridge. Might as well.

And saw that a wing fin had been carved right out of the side of the ridge itself, right in front of me.

I stared at it for a while.

The top of the fin was weathered and rounded, but below the fin, along its base, you could see the cuts and chiseling. There was even a stone brace left in place at the base of the fin, which to me looked obviously sculpted and engineered.

This kind of blew my mind. This wing fin was not supposed to be here. And while it was the first wing or fin I found at Raven Ridge? It’s been far from the last. I shot more video and took many pictures that first day, and continued discovering the entire ridgetop seemed sculpted this way — to resemble a Sea Serpent.

I also discovered a Manitou Stone carved out of the bedrock as the trail descended from the ridge on its Northeastern side, which brought me back to the Native American stonework research I’d been doing.

Authors James Mavor and Byron Dix began making the case for Native American stone workings in the Northeast in their 1989 book Manitou. They describe Manitou Stones as looking like the uper torso of a person, with a raised center and two shoulders. “These anthropomorphized stones are found throughout North America as part of Indian ritual.” They compare them to godstones, and spirit stones and the like, known to tribes in other areas.

The way the top of this stone was notched, and its center raised, as well as its sort of prominent placement led me to say, “Manitou!”

That was about all I could handle that day. I was not prepared for what I was seeing. After a time, a sort of mental overload took over — this can’t be real, right? I kept shooting video and taking pictures until the power went out on my phone, and then took mostly pictures and only a little bit of video after that, as my still camera is small and takes shaky video. Glad I did, as studying my footage and photos afterwards helped me discover more of what I’d seen, and helped me to research and prepare for my return to Raven Ridge.

But I wasn’t really prepared. It was so much bigger than I’d thought. There was so much going on there, on that ridge.

Have you ever looked at LIDAR? It’s been one of the tools I’ve employed as I’ve researched the stone works at Raven Ridge, once I figured out how to read it accurately. According to the U.S. Geological Survey:

Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) is a technology similar to RADAR that can be used to create high-resolution digital elevation models (DEMs) with vertical accuracy as good as 10 cm. LIDAR equipment, which includes a laser scanner, a Global Positioning System (GPS), and an Inertial Navigation System (INS), is generally mounted on a small aircraft. The laser scanner transmits brief laser pulses to the ground surface, from which they are reflected or scattered back to the laser scanner.

Earlier this summer I discovered the State of Vermont makes LIDAR of the entire state freely available to the public online through The Vermont Center for Geographic Information and their VT Interactive Map Viewer.

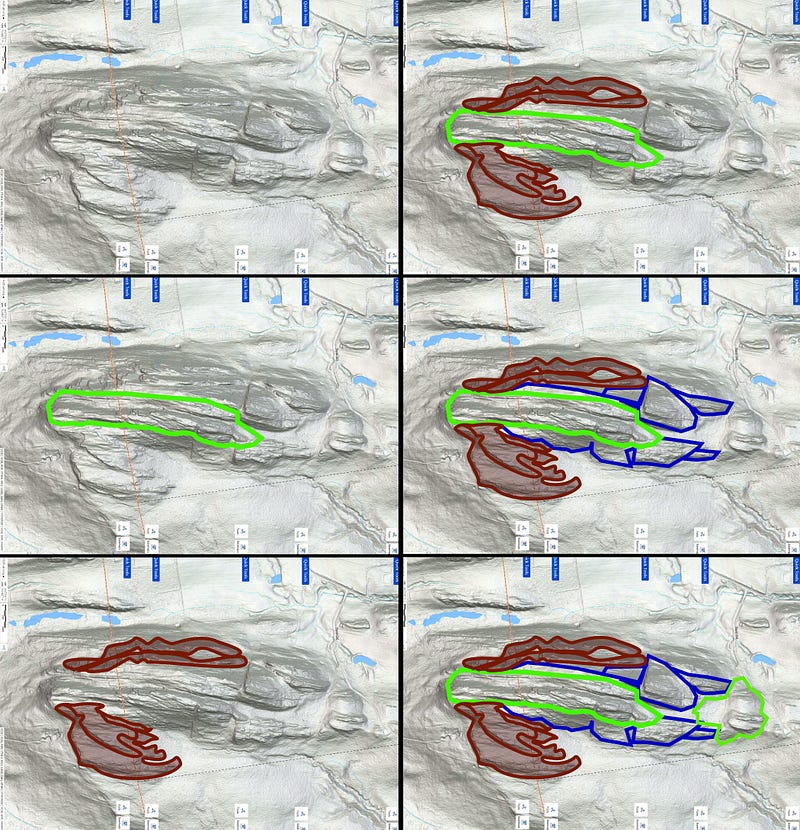

We can look at the ridge on LIDAR online and actually see the sculpted forms, the larger shaped ridges of the Serpent.

I wanted to get closer than the online viewer allowed, so I made a composite from a few views. The composite map I put together allows for study of the ridge as a whole at a more detailed resolution.

By my reckoning, the Sea Serpent is facing South, tail to the north. Its horns spread out to each side off of its head, tight against the ridge to the West and spread out to the East.

Turning the map sideways, North to the right, I’ve roughly outlined the features I believe are there: the body of the Serpent, the Great Horns, the Trailing Fins, and the long Tail. This outlining isn’t definitive, not at this point, merely subjectively suggestive at best. Nor is it alone meant to convince you.

The LIDAR image is quite striking even without the outlines — you can see some very curious features there.

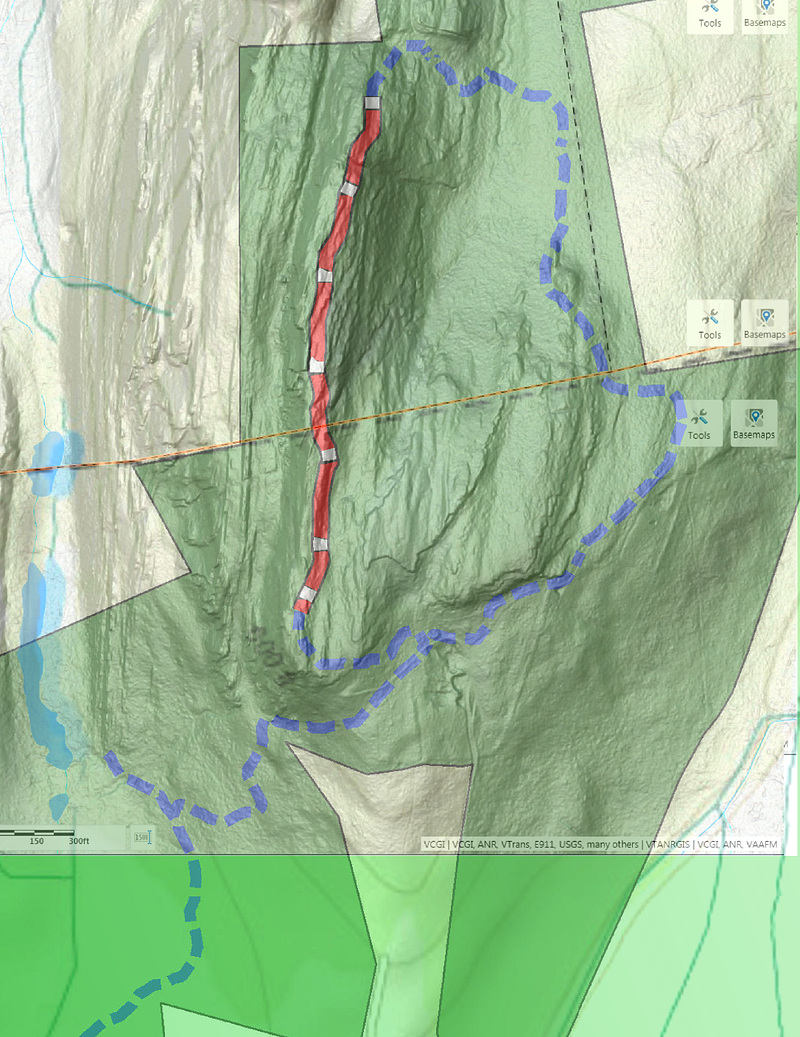

We can add The Nature Conservancy’s hiking map to the LIDAR Composite to see how in real life we approach this effigy ridge from the south, across a marsh, coming in from the bottom left in the illustration. This fully accessible trail curls off to a beaver pond on the left.

A single trail off of that accessible trail takes us up the ridge. A loop trail circles, counter-clockwise, down to the Northeast along the bluffs, North , back West and up onto the ridge itself, and then South along the ridge near to The Oven, on the Southern end.

The red-and-white dotted line on the map is the protected habitat for the ravens and bobcats. Hikers aren’t allowed up on that part of the ridge from the beginning of March until mid-June.

Below the protected ridge and The Oven on this map, the single trail leading up to the ridge takes a turn to the right, East, as it makes its way up to the loop trail. That bend in the hiking trail occurs at about the 600 foot mark. The topographical line for 600 feet for the most part mirrors the outer edge of the outlines I’ve drawn for the effigy on the LIDAR composite.

Though there is some stonework below this point on the ridge, the more representational work begins here and is present only here and higher up on the ridge. And this is likely the altitude at which The Champlain Sea would have been lapping up against Raven Ridge.

Imagine the sight, if the timing is correct! For everything above the prehistoric waterline on this ridge is worked to make the ridge appear to be the Great Horned Serpent turned to stone. As you rowed in toward it, could you be sure it was only an island, and not actually the great beast itself asleep in the shallows of the sea?

If my theories are correct, travelers pulling their boats up onto this shore of The Champlain Sea would have been greeted by a friendly Fish Effigy Map Stone and a sort of 3D Map Boat at this entrance way.

The two features are near each other in an area on the lower part of the ridge at about the 600 foot mark which feels like an entry space, although it is off the hiking trail by a few feet, at the bend in the trail pointed out above.

After outlining the Fish to highlight it’s features, I realized the shape reminded me of the area’s hiking map, turned on its side. There are raised and lowered features on the surface of the “Fish” which could be mere design, but could also represent the features of the ridge itself. It is hard to tell now under all the fuzzy green moss, but it’s not out of the question that this Fish also shows us the layout above us. It could be a Map Stone.

The “3D Map Boat,” as I’ve christened it, caught my attention on my first trip to the ridge, but I didn’t know why. Staring at it, it felt like I was missing something obvious. I shot video of it, just in case. Didn't catch the Fish on my first trip, but found it on my second when I went looking for the Boat Rock again — which then lost out for my attention to the Fish.

This is no ordinary stone with growth on the top. This is an assemblage. It was after studying the 3D LIDAR that the top of the Map Boat began to come into focus. Examining footage from the “stern” of the boat rock, I saw how much the top resembled a 3D model of the “tail” or Northern part of the ridge — although it looked like this model had been broken, the stone part broken off then laid on top by whomever accidentally damaged this ancient construct. Perhaps recently.

I’ve done my best to bring you over the Champlain Sea, and up onto the shore of our Great Horned Serpent Effigy Ridge, but I realize it may still be a little hard to wrap your head around this one. Let’s head up onto the ridge for a look at some striking features which add to the effigy evidence.

So Many Fins!

Although I’ve talked about the realism in the stone work, the representational style of so much of it, on the ridge itself the fins and skin seemed more designed to give you the feel you’re walking on the back of the Serpent, rather than trying for an exact representation, one-to-one, of what that would look like. It is still an effigy, not a theme park ride.

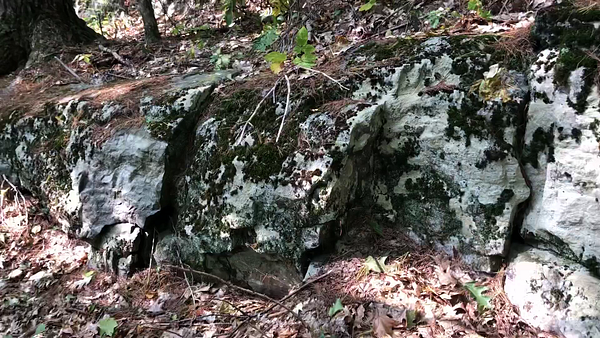

The Boulder Fin — On the ridge itself next to the fin presented earlier, a boulder has been shaped and added to create a massive wing fin, alongside a portion of the ridge carved to compliment the shape.

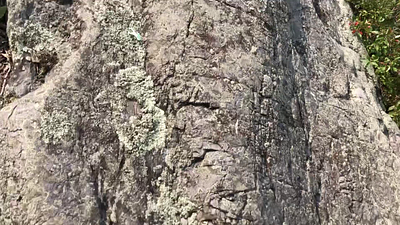

The Complex Wing Fin — This thing is wild! This complex “Wing Fin” near The Oven at Raven Ridge, shows incredible workmanship. These stones are carved to look like a wing, and fitted together, with stones underneath to prop up the boulders that make up the wing, and the assemblage is “painted” white. This is not the work of glaciers.

The wing is set at an angle off the bedrock, to accentuate its presence. The white coating — liberally applied — is of possible wood-ash based cement or paint, according to some researchers.

But Wait, There’s More — Space precludes showing you all of the fins I’ve come across at Raven Ridge — there are that many. I’ve provided these additional outlined examples to make my point.

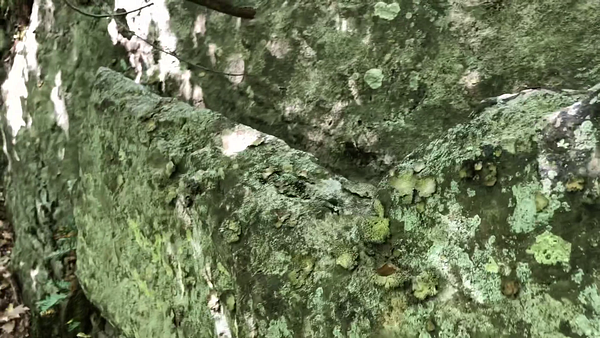

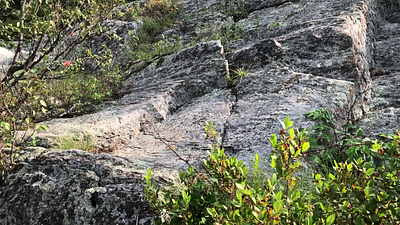

The Reptile Skin

Everywhere bedrock is exposed on the ridge, there seems to be some attempt to make it resemble the skin of a reptile, from carving the rock itself, to daubing or painting with the white wood-ash cement found prominently all over the site, to affixing small tufts of moss and daub.

The moss and even some of the painting at first appears natural, perhaps some sort of lichens, but on close inspection, these are not living bits of moss and plant matter, but dead specimens adhered to the rock surface with the wood-ash cement. As for the substance itself, The Complex Wing Fin presented above is coated with the substance and provides a good illustration of its use.

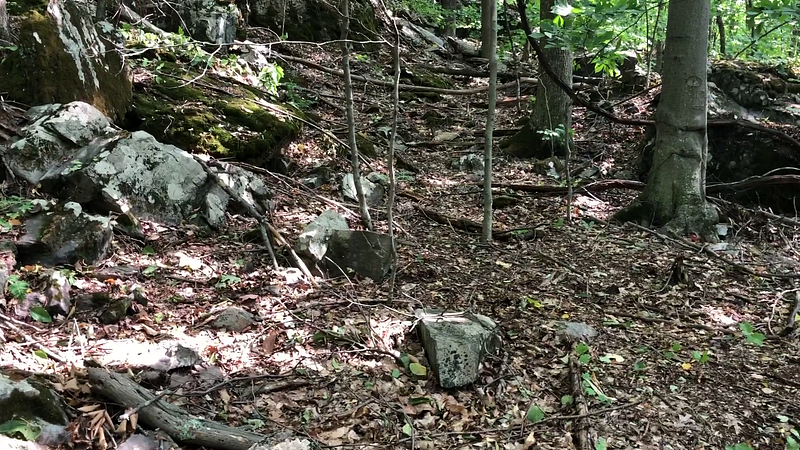

Large-Scale Ridge Work

In addition to the smaller scale work of fins and skin across the ridgetop, there are larger parts of the ridge carved, and boulders added, worked on a huge scale. Though still apparent upon close inspection, much of the work on the more gently sloping Eastern side of the ridge is obscured by years of dirt and forest cover. Human handiwork remains exposed on the steeper Western side, however.

Still, the surfaces of the cliffs on the Western side aren’t visible, except from above, looking down. Which made me curious, because whenever I looked down, I saw what appeared to be worked stone — carved bedrock, with stones and boulders added to give it the shape of the side of a Sea Serpent, the natural shape of the ridge transformed into a Sea Serpent Effigy.

I clambered down to a ledge on the Western side when things opened up on the ridge top, so I could take a look at the work. See it here for yourself — indeed, it seems the bedrock is carved and shaped, and boulders are added, to give the surface the appearance of the scaly back of a giant Sea Serpent.

The Oven is The Mouth of The Serpent.

Not ready to accept this after my first visit, on my second this became undeniable. In my first video looking at Raven Ridge after my initial visit, I speculated that the “whale” might have been the head of the Serpent. The anticline The Oven was so well known to geologists as a natural feature, I knew trying to argue that this feature had also been shaped by human hands was going to be a hard sell to academia. Seemed I wasn’t then willing to admit it, even to myself.

But the same pareidolia which leads modern folks to call it The Oven now could also have led ancient people to see a Serpent’s head inherent in the stone then, and chip away at it to “reveal” what lay beneath, led them to see teeth and a tongue. And speaking of resemblances, even now, the top of The Oven does sort of resemble Champ on the Lake Monster’s batting practice cap.

If this Sea Serpent Effigy Ridge does indeed date back to the age of The Champlain Sea, a further question arises — was the legend of a Sea Monster in Lake Champlain actually inspired by this ridge?

Could this stone Sea Monster’s legend have echoed down through the ages, even as the site itself became overgrown and lost, inspiring later stories and sightings of Champ? Could it have created the cultural expectation or normalization of the idea that a great monster inhabited the lake in the first place?

So many questions. And a couple more…

Who built this? I’m not sure. In terms of larger questions, the most straightforward explanation for “who made this?” is ancient indigenous Native Americans, locally the Abenaki and their ancestors. For that to be the case, our academic perception of who these peoples were must change. And it should, rooted in bias and racism as it currently is.

But this site requires an even greater adjustment of our perceptions than accepting Ceremonial Stone Landscapes as real, than seeing stone rows and cairns for the spiritual/natural figures they are. For as shown, the stone carving here is unusually representational in its art, and previously unseen on this scale.

Why hasn’t anyone noticed this before? Raven Ridge is a public space. People visit and hike the ridge every day. So why hasn’t anyone noticed this Sea Serpent here before? Part of the reason may be our mind’s tendency to “see” and impose form and order on inanimate objects where it is not, as our minds also compensate for this by ignoring or dismissing any forms we might think we see which our rational brains deem too outlandish to be real.

Our rational, pragmatic minds can sometimes get in the way of our perceptions and prevent us from seeing anything judged too fantastic. This makes up for that tendency we have, pareidolia, which causes us to see forms where they don’t exist, like shapes in clouds, or smiles on the fronts of cars.

These things happen subconsciously, below our normal, waking level of attention and awareness, as our minds sort out what stimuli they will let sift through their filters to our conscious brains. The features of a Sea Serpent carved and sculpted into a ridge in Vermont might not even be allowed to register consciously in many folks.

Critics may dismiss my discovery and accuse me of indulging in pareidolia myself in seeing human-worked forms in the stones of the ridge, forms which they don’t think are really there, or can be explained away as the work of glaciers. So be it, but to dismiss this evidence without evaluation seems a lazy critique to me.

I invite you to take a look at the evidence provided here and judge for yourself, as best you can from photographs and descriptions. You can also see my video presentations on Raven Ridge on YouTube: (https://www.youtube.com/c/MikeLuoma).

See It For Yourself

Pictures and video footage are no substitute for actual experience. Raven Ridge is open to the public, so you can visit and see for yourself. I am hoping for more study and appreciation of this Sea Serpent Effigy Ridge. In sharing this discovery, however, I must ask that you please honor the space if you do visit. Please don’t disturb or take anything from the site, of course, and please respect the work of The Nature Conservancy.