Rediscovering Kequasagansett

Possible Sacred Stone and Water Works Around Gates Pond in Berlin, Massachusetts

Possible Sacred Stone and Water Works Around Gates Pond in Berlin, Massachusetts

Kequasagansett?

An old town history of Berlin, Massachusetts explained that Gates Pond and its surroundings were once known to the local Indigenous Peoples as Kequasagansett. What? I’d grown up around here and never heard this.

The town history also told of how a prominent “Indian Stone” known as Sleeping Rock had marked the northwest corner of the property then known as Gates Farm at the northern base of Sawyer Hill. This was news to me, too! Though I knew there was another “Indian Stone” on a hill south of the pond, King Philip’s Rock.

I’d found a great deal of interesting, possibly Indigenous Stonework in the area around Gates Pond and Sawyer Hill, in Berlin, Massachusetts. Even a possible Sacred Stone Landscape atop that hill. Wanting to know more, I was doing a little research.

Who lived here up through the years? What did they do with the land? Where did the names come from? Was there any record of Indigenous Peoples in the area? Could they have worked in stone on these hills?

Looking into the background of Gates Pond and its environs, I discovered it was once Kequasagansett. And found that searching for answers led to a deep and interesting Indigenous History running along paths which often crossed my own.

The Reverend William A. Houghton wrote in The History of Berlin, Worcester County, Massachusetts, from 1784 to 1895 (1895) that:

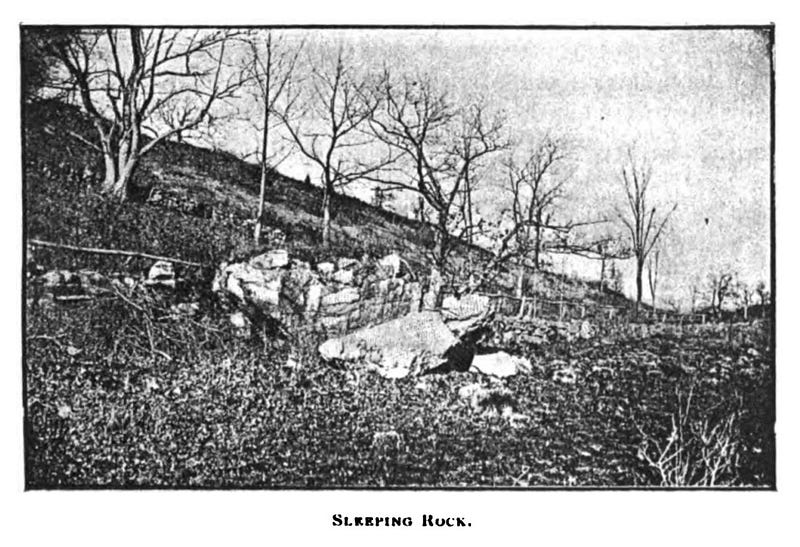

“…some minor things of slight importance have been handed down by tradition, showing that Indians have been here, — one of which, that Indians took up their abode occasionally for the night in the cavity of a certain rock, since called “Sleeping rock” situated on the Hudson Road…”

That “Sleeping Rock” was right there, north of Gates Pond.

Berlin was once part of Bolton; both were originally part of the enormous frontier town first known as Nashaway, then as Lancaster. Colonial Lancaster was the site of some bloody confrontations in King Philip’s War in the 1670’s, serving as the setting for a famous (infamous) abduction tale related by one Mary Rowlandson.

A couple of curious, later confrontations occurred with folks from right around this pond.

During Queen Ann’s War in 1705, while the area was still part of Lancaster, Indigenous Peoples allied with the French took captive men who lived at Gates Pond and carried them up to Canada.

It struck me these abducted men were carried north along routes I still travel today between my childhood home of Hudson, Massachusetts and where I live as an adult in Burlington, Vermont near Lake Champlain.

Thirty years after that abduction, Sawyer Hill to the north was said to be the site of another attempted “Indian Ambush”. The supposed-victim, grandson of an earlier abductee, claimed to have made a great, leaping getaway.

These things were evidently famous. For a while.

I’m learning much of this for the first time, however.

It is eye-opening — as so much of the Indigenous history of this area in Massachusetts has proven to be. This all happened not far from where I grew up. Yet none of this was shared in school. I’ve had to reach my fifties and do my own digging to discover this deeper history of the area.

In the 1970’s, we weren’t taught about the deep Indigenous background of our region. Yet Hudson, Massachusetts, once a part of Marlborough, made up much of the “Indian Praying Village” of Ockookangansett in the mid 1600’s. I’ve discovered a possible stone effigy row rising as a brief old stone wall in my old neighborhood.

Ockookangansett was a place where indigenous and colonial folks lived alongside each other before the wars. Where Christian Ministers attempted to convert Indigenous folks to their religion. But it’s also where Indigenous Peoples were rounded up during the first of the wars, before being exiled to an island in Boston Harbor, where many of them died.

That’s recent history. Prior to Contact, the Indigenous presence in this area stretches back millennia. Indigenous Peoples have lived in this area for thousands of years. A 4000+ year old Rockshelter with a stone wall in front, the earliest known stone structure in Massachusetts, was discovered in Flagg Swamp, a mile or so west of my childhood home, and a couple of miles southeast of Gates Pond.

The Rockshelter and its stone “wall” were excavated… and then blown up, to make way for a highway, the site and its well-documented 4000-year-old stone wall seemingly forgotten. If curious, a report on the site is available online with the State of Massachusetts.

Sacred Stonework in the Northeast?

I wandered the area around the north end of Gates Pond in Berlin, Massachusetts looking for possible Indigenous stonework thanks to ten-year old blog entries I’d been reading.

I’m following, in some cases, in the literal footsteps of folks who have been at this a lot longer than I have. One of them is Peter Waksman, proprietor of the long-running Rock Piles blog (Here’s the first of few of his entries on Gates Pond and Sawyer Hill: http://rockpiles.blogspot.com/2011/03/sawyer-hill-gates-pond-berlin-ma.html).

There is a great deal to be seen atop Sawyer Hill and down into the wetlands to its south.

There is developing recognition that Indigenous Peoples in the northeast of what’s now North America likely worked with stone — building ritual stone features, adapting the land around them, creating what have come to be known as Sacred Stone Landscapes or Ceremonial Stone Landscapes.

These constructs are all around us, but they haven’t been seen for what they truly are. The myth that this was a “New World” and a Pristine, Primitive Wilderness, and not the gardenlike, curated landscape trodden by millions of Indigenous Peoples over thousands of years it truly was, led to much of this early work being discounted or misattributed to settlers, farmers, or nature.

Some of what had been thought to be simply farmers’ “field clearing piles” and “stone walls” now are being reassessed in light of discoveries by archaeologists, antiquarians and other amateurs, and revelations from tribal representatives and elders. Much of the oldest of this work appears to be sacred stonework, often aligned with celestial objects and events.

Not all professionals are open to this concept. There remains a dogmatic belief among some archaeologists that all the stone workings of New England are Colonial. Some of this arose in the 1970’s, when the archaeological community pushed back hard against the theories of amateurs proposing stone chambers and other New England-area stone works were built by pre-Columbian European explorers.

While lecturing pre-Columbian theorists on their ignorance of 10,000 years of Indigenous Peoples’ habitation, the archaeologists themselves couldn’t conceive of the possibility that Indigenous Peoples in the Northeast had anything to do with the stone works. All were deemed colonial constructs. It was simply a given for the archaeologists that Indigenous Peoples never worked in stone.

In his 2018 book Stone Prayers, Massachusetts anthropologist and archaeologist Dr. Curtiss Hoffman faults many of his colleagues for indulging in dogmatic scientism as they maintain this attitude. This view, he says, “developed without reference to the published literature and as far as I can tell solely based on an aversive reaction to the claims of both nonprofessional and tribal groups…” Born out of backlash with no basis in fact, in other words.

It is refreshing a professional like Hoffman actively considers the mysteries of the origin of these stone works. Up until recently, avocational archaeologists, amateurs and researchers have done most of the legwork.

In fact, Hoffman cites researchers James W Mavor Jr. and Byron E Dix for their groundbreaking work, as evidenced in their 1989 book Manitou, where they proposed that New England stone chambers, walls, and other workings could be of Indigenous Peoples’ origin, basing their theories on astronomical alignments they found in the stone works.

The work done by Mavor and Dix continues to influence new generations of archaeologists, amateurs, and researchers like myself. We’re still learning from the book, from ideas and concepts Mavor and Dix introduced, figured out, or tracked down. As I study the Stone and Water Works North of Gates Pond, I still turn to Manitou for ideas on what I might be seeing… and find possible answers.

Local histories provide many details of post-contact settlement and colonization. Manitou provides insight into what may have come before.

Partial History of A Place

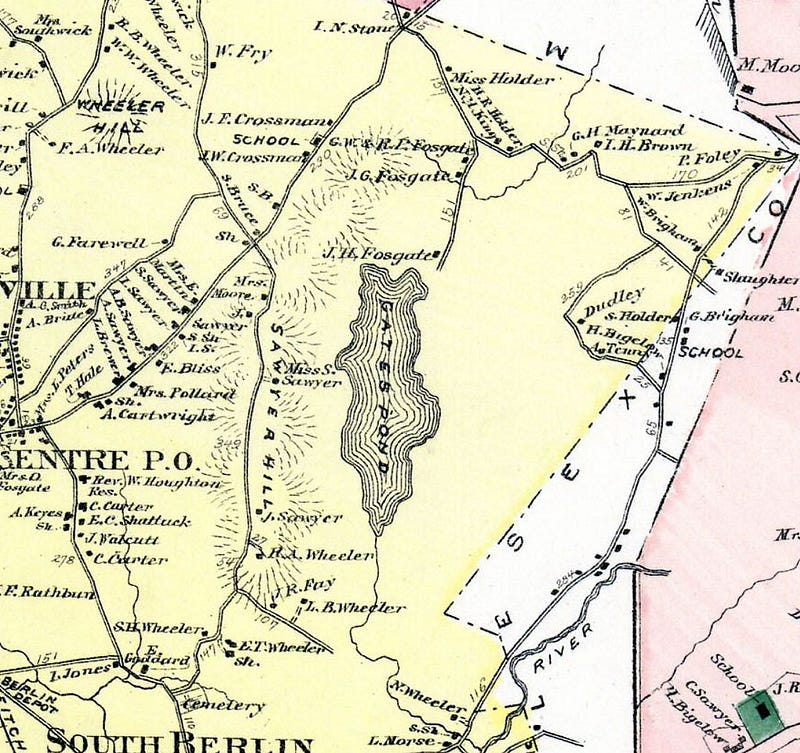

Once known as Kequasagansett, this area now bears the names of those who came later. In 1717 the tract was set off to the Estate of Stephen Gates, an early settler of Lancaster (1654), though there’s no evidence he nor any of his heirs ever lived on the land.

The Rev. Houghton, in his The History of Berlin… writes, “the description of the land and the boundaries thereof, as contained in the original set off (included)… …a considerable part of a pond lying within the said land and bounded on all sides of it by common undivided land; a rock called the Sleeping rock is on the outside of it, near the northwest corner. The place where it Lyes by the Indians was called Kequasagansett, and is laid out to the estate of the said Stephen Gates for 314 acres.”

A few years later it was sold by Gates’ heirs to Robert Fosgate, Josiah Sawyer, and others. The Sawyer family came to dominate the western side of this little corner of Berlin, Massachusetts, the Fosgates, the east.

Gates Pond and Sawyer Hill in Berlin, Massachusetts were originally in the southeastern part of Nashaway, which then became Lancaster. Bolton broke from Lancaster in 1738. Berlin later broke off from Bolton in 1784 to create an independent district. In 1812, Berlin officially became the town as it’s known today.

In the early 1600’s, many Indigenous Peoples in this region had died by plague, a Great Dying. An unknown disease, likely transmitted to them by earlier European explorers and traders, swept through their populations just prior to the arrival of the Pilgrims in 1620.

They called this entire region Whipsuppenike, “the place of sudden death”, according to the City of Marlborough’s Historical Commission (The Lords of Whipsuppenike — History of Marlborough: https://www.marlborough-ma.gov/historical-commission/pages/lords-whipsuppenike).

As part of the early frontier, this region was the first arena where invading and indigenous cultures violently clashed. Despite this, and perhaps due to the Great Dying, many later settlers of Berlin came to believe Indigenous Peoples never lived in the territory comprising the town: “No records extent nor Indian relics point to the fact of any permanent lodgment within what is now Berlin territory,” Houghton wrote, reinforcing the all-too-common trope that Indigenous Peoples didn’t live in that place, they just passed through it, or fished or hunted there.

In contrast, Houghton noted that “Clamshell (Pond, in Clinton), as also Gates Pond, was nearly in a Direct Line between the Ockoocangansetts in Marlborough and Nashaways at Washacum, hence the trail leading from one place to the other would necessarily pass through this town and by these ponds.”

The Sawyer family were involved in two of the more notable historic interactions with Indigenous Peoples in the first half of the 18th century.

The first was an abduction amidst one of the early wars between colonists and the Indigenous Peoples. Three settlers were abducted from Lancaster and “brought to Canada”, including one Thomas Sawyer Jr, the grandson of early settler Josiah. During Queen Ann’s War in October of 1705, Thomas, Jr., his son Elias, and John Bigelow of Marlborough were abducted from Thomas’ saw-mill just south of the pond.

The city of Marlborough’s online history mentions this incident among other abductions (though it gives prominence to Bigelow, the city resident) and reports, “there were many raids made here by Indians from the vicinity of Montreal, who would come down Lake Champlain and across Vermont and then strike easterly to annoy the English towns of Massachusetts. Marlborough was usually the place nearest to Boston to feel these raids…”

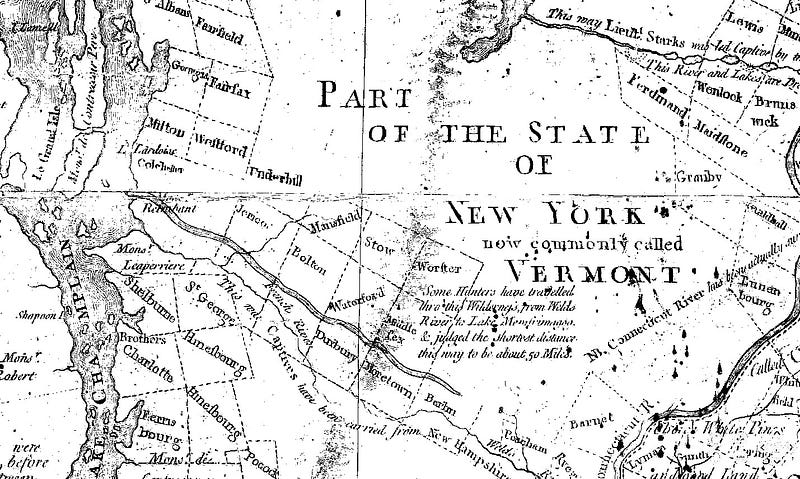

Captives like Bigelow and the Sawyers were likely brought up trails and along rivers like the Merrimack, the Connecticut, and the White. And, according to the Detail from a 1784 map of the “Province of New Hampshire” shared by historian Bob Blanchard on Facebook (created by Abel Sawyer for John Hancock, then-governor of Massachusetts, and for the “Honorable Council of the State of New Hampshire”), in the Burlington, Vermont area, “Indians” carried captives from the south (the Map says New Hampshire) along the Winooski River (The French River on the Map), which rolls along less than a mile from my present home on its way to Lake Champlain.

A few days before visiting Gates Pond, I’d walked along the banks of the Winooski River near my home in Burlington, Vermont. Headed to my old hometown of Hudson, Massachusetts for a holiday visit, and on Tuesday and Wednesday, spent hours roaming around Gates Pond and Sawyer Hill in Berlin.

Afterwards, researching the pond’s history and reading about this abduction, the resonances between their history and my reality shook me. These men lived in the area where I once lived. They were abducted and brought up through the area where I live now, along paths I’d followed for years, as I traveled between where I grew up and where I chose to live my adult life.

There is a certain resonance, as if I’m walking through history in these places, in experiencing these spaces. Learning the stories brings this history alive — it echoes around me, and, somehow, these areas now feel connected in a greater than personal way.

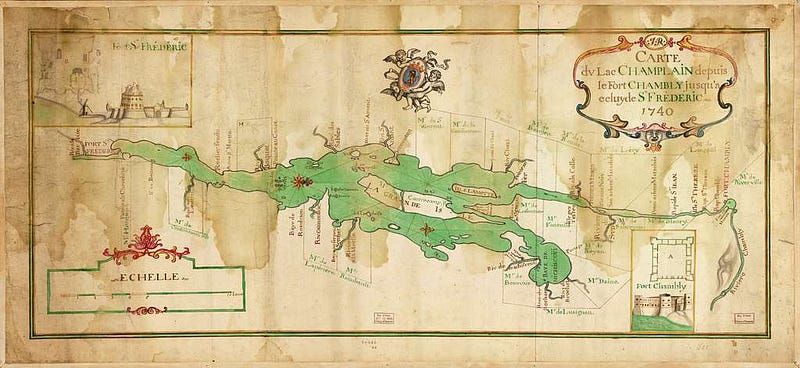

The men were taken up past Burlington on Lake Champlain, and then on up the Richelieu River. The Richelieu at the time was called the Chambly River or Iroquois River by Europeans, and Masoliantekw (‘water where there’s lots of food’) by the Abenaki.

At Fort Chambly near Montreal, Thomas Sawyer Jr. negotiated for his freedom by agreeing to build Canada’s first saw-mill, financed by Governour Claude de Ramezay of Montreal and Francois Hertel de LaFresniere, the Seigneur de Chambly.

It’s said the Indigenous Peoples, having freed Elias Sawyer and Bigelow, were loathe at first to let Thomas go, too, forcing local French officials to resort to trickery to get their “Christianized Indians” to cooperate. The Governour of Montreal and Father Theiry said they would unlock the gates of Purgatory with a giant key they brandished, and the Indians would be pulled in, unless they set Thomas free. The Indigenous folks agreed to let the man go. The French authorities put the key away.

Sawyer built the sawmill, and he and Bigelow were freed to return home to Massachusetts, though his son Elias was forced to remain for an additional year to help run the mill. [Some additional details from “A French and Indian Wars Enigma” by Beatrice Couture Sawyer in Je Me Souviens — A Publication of the American French Genealogical Society Vol. X, №1., Summer 1981.]

According to the Fort Chambly website, in the fall of 2011, when digging for a new project, they discovered the foundations of that first seigniorial mill at Fort Chambly, built by old Thomas Sawyer, Jr.

Sawyer and his progeny evidently were known for building mills, this misadventure seemingly adding to their renown. After relating the tale, Houghton exclaimed, “No wonder the Sawyers have had sawmill ‘on the brain’. If you can find a sawmill in all this region not started or run by a Sawyer, publish it!”

Houghton reported that Thomas Sawyer Jr.’s eldest son William Sawyer owned 100 acres of land on the West slope of Gates Hill, which is now Sawyer Hill, and 120 on the east slope. Also said to be on the hill were his sons William, Josiah, and Aholiab. It was this Josiah, later a Deacon, who was said to have been ambushed by an Indigenous Person and who made an amazing leap to escape.

The town historian believed the family story: “The tradition of the Sawyer family of the remarkable leap of their ancestor here Deacon Josiah Sawyer, is undoubtedly substantially true, and worthy of record,” Houghton wrote.

According to the History, Deacon Josiah Sawyer became the owner of a tract of land on Sawyer Hill sometime around 1735. While clearing the land and making preparation to settle there, he was living in Bolton with his father. He was returning home one evening on foot, as was his custom, and:

“…in descending the hill just north of the Quaker Meeting-house, an Indian, in ambush by the wayside, sprang out with tomahawk in hand. Sawyer, being unprepared with defensive weapons, took to his heels, with the Indian after him. He, by his agility, outran the savage and reached his home in safety. By measurement the next day, it was found that one of the leaps, as the footprints showed, was sixteen feet, the most extraordinary leap ever known in these parts.”

It’s a good story. Maybe even true.

It struck me that the top of that slope, where the story begins, is where I found enormous stones and small boulders augmented and perched. And the climax of the tale, The Leap, down by the road, occurred near Sleeping Rock. Although, like the story of The Leap, I didn’t know about Sleeping Rock until later, after doing further research following up on my visits.

I did find an enormous boulder on that slope, but I don’t think it’s the Sleeping Rock, as it doesn’t look like the old black-and-white image. And if I’m understanding the descriptions correctly, it seems like Sleeping Rock should be a little further west, and closer to the road. Houghton:

The rock South of the Hudson Rd, between Captain Silas Sawyer’s and George H. Bruce’s, has been known as Sleeping Rock from the early times, so named in some of the first deeds. The origin of the name appears to have been from the fact that Indians occasionally used it as a shelter and to sleep under, — two were known so to do, says tradition. A shelving part has probably fallen over since that time. This rock was a corner of the original Gates farm. The place was called by the Indians the same as the name of the pond, Kequasagansett.

I haven’t seen a boulder like it along “…the Hudson Rd…” — Route 62 — so I don’t know if the original Sleeping Rock is still around. Still, it strikes me… An “Indian Stone” known as Sleeping Rock used as a marker in the earliest known deeds to this place once called Kequasagansett. A place the Indigenous Peoples just… passed through?

The Fosgates’ history on the land wasn’t quite as eventful as the Sawyers. The Fosgates lived on Gates farm starting in the 1750s. Lucas Fosgate joined the Shakers in the 1860s, and his sons divided up the old farm. Grandson Frederick Fosgate ran the picnic grounds at Gates Pond and had several cottages on the Eastern Shore.

That could have been a lucrative gig, for a time. According to Houghton, the pond was quite the place towards the end of the 19th century:

This beautiful lake of pure, cold, crystal water, fed by springs, is the favorite resort of pleasure seekers and picnic parties in the summer season; the eastern shore is studded with cottages and houses for entertainment. On the western acclivity is Lake Side, so named by Madame Rudersdoff, the famous singer, who lived there a few years ago.

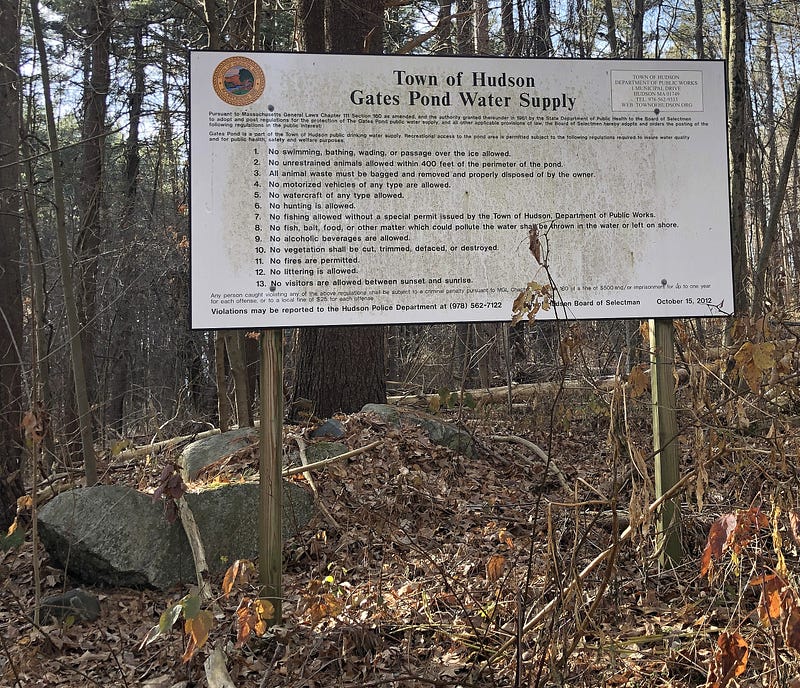

That all changed. The next door town of Hudson need a new water supply, and the town petitioned the Massachusetts legislature in 1883 to give Hudson eminent domain to take Gates Pond for a clean public water supply, which they did.

The town took over the pond and its surroundings. Although Hudson now primarily relies on wells for its public water supply, Gates Pond remains an auxiliary supply.

At the advice of the State Board of Health, Hudson eventually razed all buildings on the land surrounding the pond.

In 1901, the Fosgates sued the town for damages, as the town’s taking of the water rights around Gates Pond stopped the water from flowing in two brooks across their pastures downstream.

Today, six lanes of superhighway Interstate 495 run through the old Gates Farm. The old Fosgate place is a world away from the pond, as Fosgate Road dead-ends on the other side of the highway. And Gates Pond Road no longer goes to Gates Pond.

Whence These Waterworks?

Venturing into the woods north of Gates Pond, I wandered in along what at first seemed to be a raised roadbed, but which narrowed considerably as I walked, proving it was no road. Instead, it seemed stone-lined or stone-constructed berms were lining the sides of a watercourse, and I was on the left side.

I was surprised to find this water feature on Google Maps. The ditches do not appear as orderly as they do on the map, however. Older works, not depicted, seem to branch off as well. And stone walls or stone rows rise up out of the ditches, in some cases seemingly constructed with them.

Were there mills here? While I discovered there were sawmills near Gates Pond, they were along the southern end, where Thomas Sawyer Jr. was abducted. There’s no mention of any waterworks or anything like this on the North End of the pond.

The Southern Bank here seemed to be entirely constructed, made up of stone.

Questions began to arise in my mind.

Could it be natural? Not likely…

Could it be mundane? Recent? Gates Pond has been part of a public water supply, it could be the town’s old work.

Or could it be from before that, perhaps farmers’ irrigation ditches?

As I walked along the bank which seemed artificially made, there was a great deal of stone to be seen in its possible construction, and more strewn around and about from its slow deconstruction. It occurred to me it would be nice to find something provably constructed in the stony bank — that would help answer some questions.

And that’s when I found the stone-lined spring.

In that bank.

It was surprisingly hard to capture well on camera.

Further back into the woods, barely visible among the fresh blanket of fallen leaves, a U-Shaped assemblage stood out and caught my attention, on the north side, toward the back or west of the waterworks north of the pond.

Both of these stone structures created more questions than answers. Yet they were clearly constructions.

It’s hard to say how extensive the ditches of the Water Works were. And they do seem quite old. There are also boulders in these stone lined ditches which look like they could have been primitive sluice gates, to allow or block water flow. Were these ancient mill races? Later town water works?

Maybe the Town of Hudson built these? Trying to clean up the swamp water? There are records of them doing this next to the pond. In the years after acquiring the pond for the town’s water supply, the town attempted to find ways to increase the flow of water into the pond.

Towards the end of the 19th Century, the town managed to expand and filter the last section of Fosgate Brook, converting it from swampland. This now simply appears to be the north end of the pond — and you can see how the pond has enlarged when you look at the old and new maps I’ve been sharing.

They wrote of digging ditches around the swamp. It could be that this is simply an example of that work.

But… what if that work was done on top of older work? Making use of what had been done here, long before? I had to wonder. The stone work towards the “back” grew very curious in appearance.

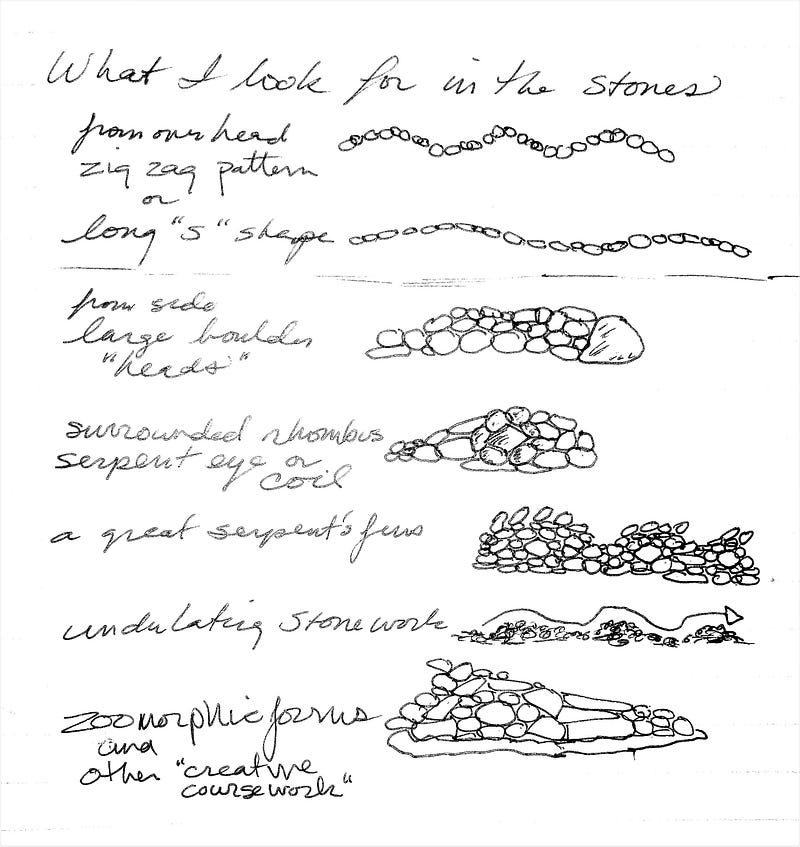

Ancient, serpentine stone rows rise from the western and northern edges at the back of the wetlands, in some cases snaking right up out of the ditches. Some end abruptly, or follow strange curving short courses. The stones are not flat stones laid out in even, overlapping courses, but boulders and stones of many shapes and sizes, combined in construction in creative ways — undulating courses and nonsensical shapes.

Nonsensical, that is, until one realizes they are consistently suggestive of serpents, and turtles, presented in Indigenous effigy forms. These old stone rows towards the back of the wetlands and waterworks had the look of indigenous stone work. It reminded me of work I’d seen covered before.

Mavor and Dix wrote about possible Indigenous Peoples’ stone work involving waterworks in their groundbreaking study MANITOU.

Their research on stone work involved with waterways concentrated on Boxborough, about 15 miles northeast of here. Some of the work they describe and picture is remarkably similar to what we see here at Gates Pond.

Crediting the Indigenous folks with extensive water and stone works in the Boxborough area, Mavor and Dix write:

But by far the most important artifacts left by the native inhabitants of the Nashoba region were the elements of ritual architecture on the landscape. The historical record includes a description of a water management system engineered and constructed by Indians and later reused by colonists to power a sawmill. Also, the Nashoba villagers built two earthen dams and ditch systems that connected three brooks near what is now called Shaker Lane. “In the spring it made them a good supply.” This type of system was common among native New Englanders, and there is a specific Algonquian word for it, Pemmoquittaquomut, meaning “ponds joined by a ditch.”

Mavor and Dix’s stone work and waterworks were next to the “Indian Praying Village” just to the North, Nashoba, now mostly the town of Littleton, Massachusetts.

These water works North of Gates Pond are next to the “Indian Praying Village” of Ockoocangansett, most of which is now Hudson, Massachusetts.

Nashoba, Ockoocangansett, and Hassanamessit, the “Indian Praying Village” which later became Grafton, about 15 miles southwest of here, were all established by the Reverend John Eliot in May of 1654 in what was then Nipmuc / Nashaway territory. The Indigenous families of these villages were said by Mavor and Dix to be interrelated in ways the Europeans didn’t understand at the time.

Perhaps these waterworks are interrelated as well.

These possibilities are part of what got me searching for answers, looking into the history of Gates Pond, and Sawyer Hill. I’m still looking.

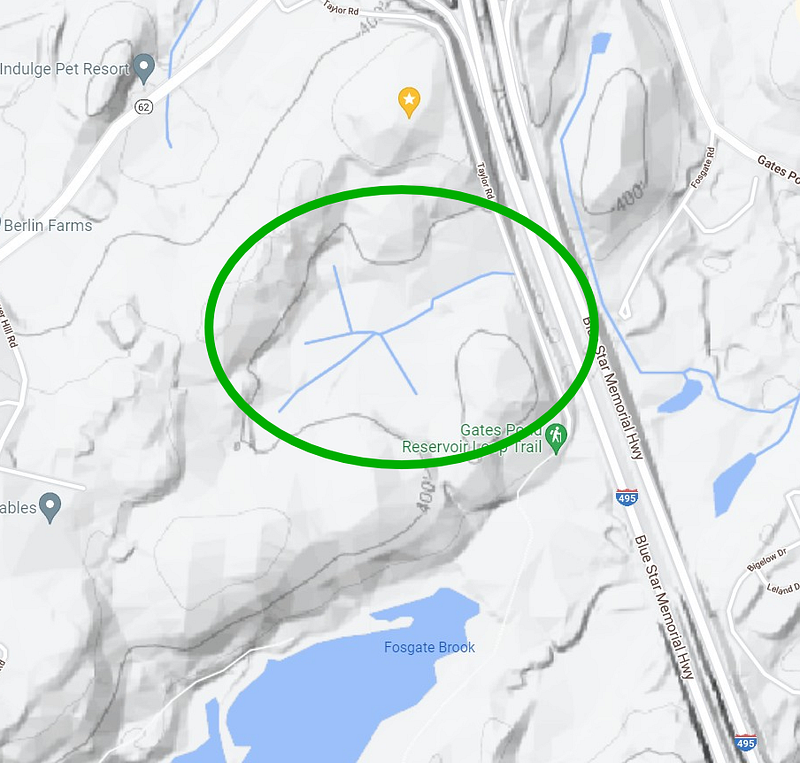

It can be confusing — this entire series of hills that circle the north and west sides of Gates Pond are called, in the singular, Sawyer Hill. I’ve shared a larger USGS Map of the area to show this, and another, cropped part of that map for detail of the hill I’m covering.

On the detail map, the light green circle shows a field of interesting stone features gathered around the summit of the hill, the darker circle to the south encircles the area of these water walls. The burnt orange line is the massive stone row which runs from the wetlands and up and over the northernmost Sawyer Hill.

There are possible effigy forms in these swampy stone rows. Often, the effigies are serpent forms. Take a look at the outlined example:

One note — the large round stone may not be intended to be the eye of the Serpent, but could instead be an egg in the Serpent’s Mouth, with the smaller round stone to the left meant to represent the actual eye.

Before we look at more of the stone rows, let me share a page from my notebook on what it is I look for in the stonework in terms of identifying possible Indigenous forms.

Maybe you can spot the signs in some of these wetland stone rows:

Up & Out of The Wetlands —The Central Stone Row

While the wetland walls aren’t very long, for the most part, and surround somewhat small areas when they seem to have a practical function at all, one of the stone rows separates itself from the others and storms north all the way up Sawyer Hill, splitting the hilltop in half.

As the stonework on top of the hill grows more intriguing, so does the make-up of this singular stone row as it crests the hilltop and slithers down the northern slope.

As the central stone row rises up and over the hill, several large boulders are incorporated into it, as well as prominent protrusions and outcrops of bedrock.

Two other stone rows branch off it to run west, each with a short tag of a row to the east at the intersection with the bigger row.

This stone row shows off possible effigy work as it rises. This work becomes quite evident on the hilltop itself, where the stone row displays serpentine features and incorporates boulders as snake-like “heads” among the stone “scales”.

There are several possible Manitou Stones set sideways along the stone row, as well as possible fin- or wing-shaped stones, possibly indicative of Great Serpent stone row effigy work.

There are times this stone row seems somewhat ordinary; other times, it’s extraordinary. Given the shorter, serpentine stone rows we find in the wetlands and a little lower on the northwestern hilltop, it’s likely parts of this long, central stone row were adapted from Indigenous work by the settlers here. Perhaps the Sawyers themselves “repaired” or turned separate Serpent Stone Rows into a property marker.

The stone row does seem to serve as a dividing line, of sorts, especially on top of the hill. Although there are interesting possible remnants of stonework all over the high spot, the area to the east of the stone row seems to have been more cultivated, leaving less behind.

Atop the hill, several boulders dot the central section on the eastern side, while on the western side we find larger boulders and more ornate groupings of stones, with more boulders left in place.

Some of the boulders and outcrops on the western side have stones placed atop them, but these are not likely clearing piles, as this side of the hill does not appear to have been cleared of stones, and so are quite possibly Manitou Hassanash — Spirit Stones.

The Eastern Side of the Central Stone Row

Although somewhat drier than the swamp to the south and west, the lower hillside area was still a bit marshy, covered in years of fallen leaves now covered by a fresh coating. As it had been raining for a few days earlier in the week, everything just a little… moist.

At this southern base of Sawyer Hill, there are several cases where strangely split stones sit in groups next to hollows in the ground.

Though perhaps some hollows and splits stones are attributable to the damage root systems do to stones they entangle with and later dredge up as the old tree falls over, uprooted, there are larger possible, more deliberate looking rockpiles next to these hollows once we begin to climb the hill.

Climbing the hill, we begin to see more stones stacked and arranged. A possible wing shape stone sits atop a cliff and appears deliberately perched there.

Still, the stonework on this eastern hillside side pales in comparison to what I found on the other side of the hill. My thought was that, perhaps, this was due to the fact this side appears to have been more settled.

As I finished climbing and made my way around the eastern side of the somewhat circular hilltop, I could not shake a developing impression that the boulders on this eastern side were all actually pointing up and in towards the center, toward the top of the hill. This was only an impression, but it would be worth a check in the future, if the stones remain.

Geologists like to proclaim, “Those are glacial erratics!” whenever we point to boulders which are seemingly out of place on the landscape in New England. My answer is, “Of course they are. And then?”

People were here for at least 10,000 years, and millions of people lived on this land over that period of time. We know of some living specifically in this area, in the nearby (though now-destroyed) Flagg Rockshelter, some 4-5000 years ago.

Do you think we can allow for Indigenous peoples having moved some stones around? Given that, on this hilltop, we’re a mere stone’s throw from an “Indian Stone” — Sleeping Rock? And another, King Philip’s Rock, is found just south of the pond?

They seem to have moved some stones around the summits of Sawyer Hill. There are curious stones all around the crest of this hill which seem to point upward.

And… the stones and boulders on the western side of the stone row are even a bit more curious-looking than these on the east.

The Western Side of the Central Stone Row

“And Then?”

A word or two about geology. As mentioned when discussing the boulders on the eastern side, I’m not denying glaciers are likely responsible for depositing many of these boulders in this general vicinity. I am suggesting that’s only part of the story here. What happened to the stones after they were moved by the glaciers?

Millions of human beings ranged across this landscape for over 10,000 years before European colonists arrived. This was no Pristine Wilderness, although that myth was developed and encouraged by the descendants of those who later settled here.

How many mistaken assumptions about the nature of geology have arisen from the myth of the Pristine Wilderness? How many have stemmed from the second operative lie we hear far too often to be true, “Indians never lived here, they only passed through and hunted or fished here?”

This second lie gives comfort to many who otherwise would have to admit they live on stolen land. But maintaining it displays a callous indifference and ignorance towards the nomadic way of life lived by Indigenous Peoples in ancient northeastern North America, who spent different seasons of the year in different places, ranging across an entire landscape, not confined to a few “improved” acres, the Europeans’ standard for “living in a place”.

History is being rewritten, and previously unknown histories uncovered, as Indigenous authors and Indigenous sources provide necessary, corrective viewpoints on the larger history of North America. This is sometimes called “Decolonizing” History. Or Decolonizing anthropology. Or Decolonizing archaeology.

Geology could also use some Decolonizing, some reckoning with the assumptions made in its past which were dependent upon these lies of a Pristine Wilderness and lack of habitation, which we now know were untrue. Science should be based on facts.

Offering a geological explanation for any stone work is neither an end point nor a closing argument, but the preface to a discussion which begins, “And Then?”

“And Then?”

The “Indians” Named Prominent Stones.

For Indigenous Peoples in the Northeastern part of what is now North America, enormous boulders were more than landmarks. Somehow, they bore witness — acted as official watchers to momentous events.

To the north of here, in Princeton, Massachusetts — a place, like Berlin, once part of larger, frontier Lancaster — we find Redemption Rock, where a major hostage and peacemaking exchange took place in 1676 during the first bloody war between colonists and Indigenous Peoples being forced from their lands.

To the south of the pond here, on a hill, we find King Philip’s Rock, a prominent boulder named for the Indigenous leader of unified Indigenous Peoples in that first conflict, said to be a meeting place for him and his warriors before and after battles in Lancaster and Marlborough. Metacom, a Wampanoag, a son of Massassoit who had worked with the Plymouth settlers, was known to the Europeans as “Philip”.

This is not the only King Philip’s Rock. Three or four large boulders around this part of Central Massachusetts bear this name.

We saw earlier a prominent boulder associated with local Indigenous Peoples, Sleeping Rock, downslope northwest of here. As William Houghton related in his history of Berlin, it’s been “known as Sleeping Rock from the early times, so named in some of the first deeds. The origin of the name appears to have been from the fact that Indians occasionally used it as a shelter and to sleep under… ”

Sleeping Rock. King Philip’s Rock(s). Redemption Rock. There are more — innumerable other “Indian Stones” lay around the Northeast, referenced in local histories and small towns’ oral traditions. These names are obvious, historical evidence of a deep and meaningful association between Indigenous Peoples of the Northeast and Prominent Stones.

One more morsel of food for thought — recall that the earliest constructed stone row discovered in Massachusetts was excavated only a couple of miles south of here in Marlborough’s Flagg Swamp: a 4000 year-old stone “wall” uncovered at an ancient rockshelter.

The evidence is there. And perhaps here at Gates Pond. Indigenous Peoples in the Northeast worked with stone. Not carving stone with a metal chisel — though the European settlers did indeed carve the bargain at Redemption Rock into the stone — but moving stones, chipping stones, working stone with stone, perching stone on stone.

Some confusion can greet the idea of Indigenous Peoples working with stone in the Northeast when it’s first encountered. Hearing that some of the old stone “walls”, stone “chambers” and stone “cairns” may pre-date European settlement and be of Indigenous origin, and that Indigenous Peoples worked with stone in this area, some assume further European-style stone-working is being claimed, and reject the entire idea outright — but that sort of stone-working is not the case being argued.

In some of these Indigenous stone constructs, we may see some resemblances to similar European structures. It would be a mistake, however, to “read” these forms through the filter of a different culture, and extrapolate from there. Instead, we want to attempt to Decolonize our concepts of what it means to Work with Stone.

What does it mean to work with stone in this way?

Perhaps it means not to construct grand idols or palaces, but instead to recognize Prominent Stones as such, already present in nature. Perhaps it’s not to bind or lay any claim on the land using stone but instead to augment what already emerges in the bedrock of ridges and ledges. And, possibly, not to pen in animals with stone but to celebrate animal-like spirits in effigy, seemingly already present in the forms of some of the stones.

There are some Prominent Stones present on the Western side of the hilltop.

Crossing the central stone row and climbing back up towards the hilltop on the western side, I became slowly, steadily more awestruck by the stones and the possible work I was observing.

One cluster featured split stones, including a triple-split triangular stone, others around it on the ground, the splits propped and wedged open.

Several large and somewhat flat boulders share the space near the hilltop. An enormous boulder sits up near the top on the northwestern hillside.

A large stone which may have wedged off of the original boulder appears to have been worked, turned and perched to give the look of a fin. A smaller one may have been meant to suggest a tooth.

This boulder seemed to be Something. But I don’t know what.

When I first read of “Sleeping Rock”, I thought this could be a candidate for it, having just seen it. But as I read the description now, I think Sleeping Rock was further down the hill, closer to the roadway. I’ve not found it to date.

The western hillside is a bit more rugged and wooded, which is perhaps why some remnants of old work remain.

Like the pointing stones, this lower western stone work seems to encircle the top of the hill, giving me the sense there was perhaps a sort of Sacred Precinct atop this hill.

This was reinforced as I found boulders with prayer stones atop them, alongside extremely old, very short, curving stone rows, and more possible Manitou Hassanash — possible Ceremonial Stone Landscape work.

Some of this looked like what Peter Waksman had shared on his Rock Piles blog, although perhaps a bit more run down by weather in the decade since.

As following this stone work brought me around the hill, I was once again among the “water walls” towards the “back” of the waterworks, the stone work rising up the hill from the wetland’s northwestern corner.

Heading Up That Hill, Too

Ahead, a western-leading stone row branched off of the central stone row. After wending back and forth a bit it “straightened up” and became the boundary “wall” of an orchard, climbing a hill to my southwest. Had there been something on Rock Piles about that hill, too?

Apparently, I wasn’t through exploring the northern reaches of Kequasagansett just yet.

Two larger stone rows branch off perpendicular from the Central Stone Row and run westward. This one wends in a subtle zig-zag fashion before straightening up to become a boundary. It starts following an orchard fence, setting the other side off-limits, as it winds down through the valley and up another hill — another summit of Sawyers Hill.

Yet, even as it “straightens” out, its courses still undulate up and down horizontally in a serpentine fashion, albeit in a straighter vertical line across the landscape.

Some dismiss the possibility that a stone row is an effigy row if it marks a property boundary. I don’t consider the usage of a stone row as a boundary a disqualification from possible effigy origins, because I do not agree that this establishes the age of the stone row in a time-frame post-dating when the boundary was drawn.

Which came first? The stone row may pre-date the boundary line, especially as in this case, where only part of the stone row seems employed as the boundary itself.

Even along the orchard there are several potential effigy forms built into the stone row. Serpents on Serpents. Effigies all along its length.

On the hill, in the orchard inside the fence, glacial erratics are partially visible.

Another fence runs along the top of the hill, rendering this hilltop a dead end.

Looking around outside the fences, near the top of this hill, alongside the stone row, I found several additional interesting stone features.

Boulders appeared to have prayer stones atop, possibly accompanied by wing shaped stones or fin shaped stones.

And more split rocks appeared alongside this stone row as I made my way back to the Central Stone Row.

Following the central stone row, I found my way back downhill and then made my way out through the water works to the access road to Gates Pond.

Returning to my car on my second day of November explorations, the remnants of a stone wall on the bank behind me struck me as another possible old serpentine stone row.

It was a reminder there was still a lot to see here at Gates Pond.

Diving deeper into research, I’d soon discover this place was known as Kequasagansett and learn its history. And discover the way the history here resonated with my own experiences.

Looking ahead, I’d be back in a month to find King Philip’s Rock and to finally make a full circuit of the pond — in my three visits as an adult thus far, I’d not gone all the way around. Gotten distracted, each time.

Looking back, I realized that the discoveries I’d made last year in December 2020 could be connected with the wetlands and waterworks I’d been checking out this year, just separated now by a cell tower. Wanted to go through what I’d gathered then and take another look.

There was more to do. And a lot to process! This was merely the start of rediscovering Kequasagansett, its history as deep as the pure, cold waters of the placid pond itself.

Correction: Earlier versions of this story reported that the abduction of three men in 1705 took place just south of Gates Pond. I’ve been told this is incorrect, and that the abduction took place further north, in what is still Lancaster proper, near Four Ponds.