Re-Learning History — From Where To Here?

New Study Paints Increasingly Complex Picture of Early North America

New Study Paints Increasingly Complex Picture of Early North America

How did people first come to the Americas? It didn’t happen the way we were taught in school, years ago. Scientists are discovering a diversity among ancient North Americans which shows our former ideas of how populations first migrated to this continent are simplistic and incomplete at best. The old models are flawed… and now, out of date.

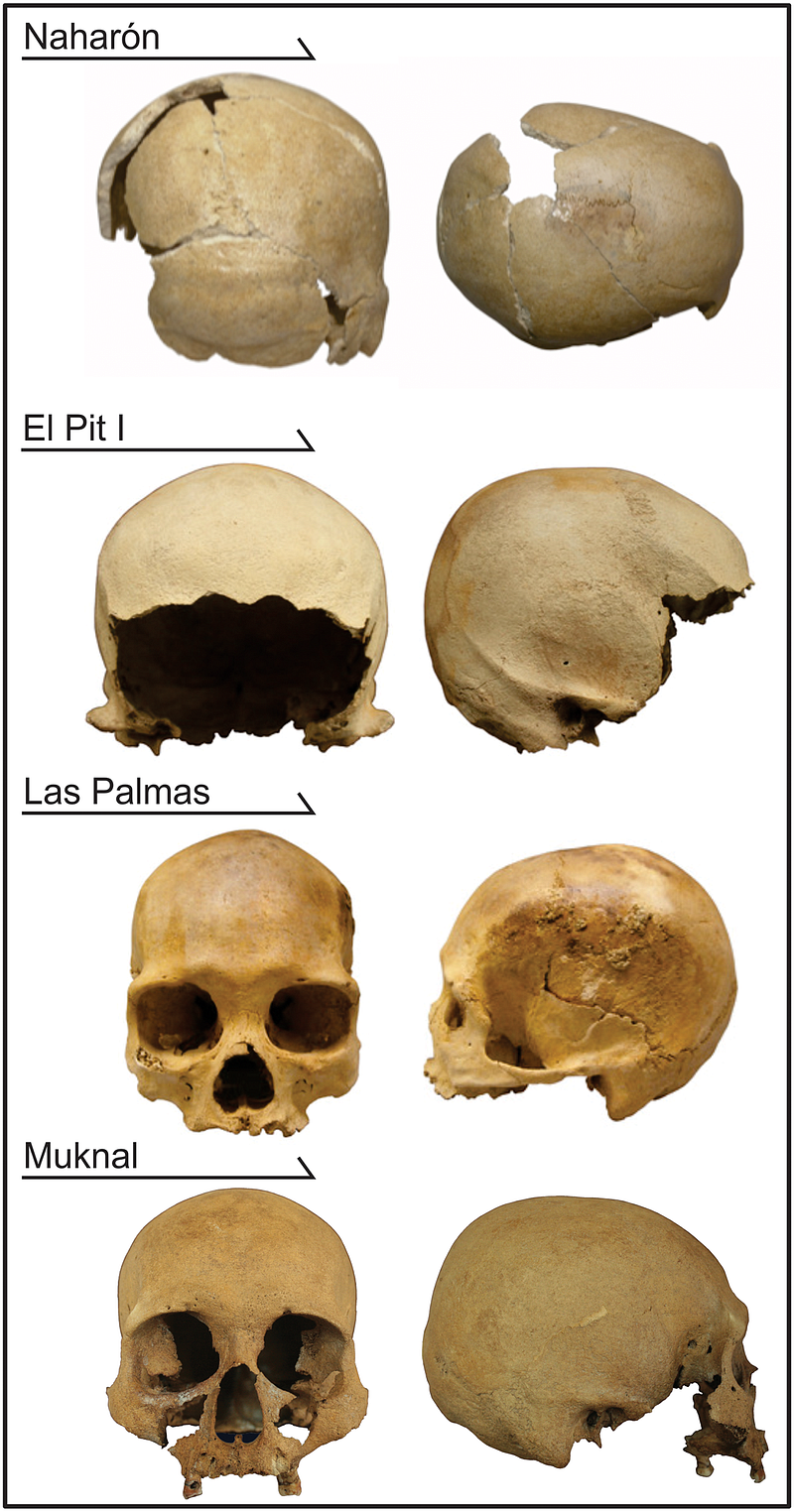

The new study released by researchers at The Ohio State University Department of Anthropology this week shows conventional theories about the settling of North and South America need to be reexamined. They compared the shape and structure, or craniofacial morphology, of four skulls found at Quintana Roo, on the Yucatan peninsula near Tulum, Mexico, which dated back to around the time of the end of the last Ice Age, and discovered a surprising diversity among them.

“The first Americans were much more complex, much more diverse than we thought,” said Mark Hubbe, professor of anthropology at The Ohio State University and co-lead author of the study. “We have always talked about the settlement of the Americas as if North America and South America were the same. But they are different continents with different stories of how they were settled.”[i]

Alejandro Terrazas Mata of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Mexico joined Hubbe in the study. The skulls were discovered 2008 and 2015 in submerged caves. Though underwater now, when the four people were living, the caves were above sea level.

For a long time, we believed modern humans came to the Americas from Northeast Asia across a land bridge in the Bering Strait around 12–13,000 years ago, then traveled down between the two glaciers covering northern North America and populated North and then South America, rather quickly. The settlers were thought to be exclusively from Northeast Asia, and to have traveled exclusively over land — over the Bering Land Bridge — any sea voyages were ruled out.

We know now this was not the case. That model was far too simplistic to describe what now appears to have been a much more complex population dispersal throughout the Americas.

New knowledge came our way about fifteen years ago, when we determined that South American settlement came in two distinct waves. Studies such as those of 81 skulls found at Lagoa Santa, Brazil, reported in 2005, discovered that later populations of prehistoric, recent, and present Native Americans tend to have skulls similar to late and modern Northern Asians, but that “the earliest South Americans tend to be more similar to present Australians, Melanesians, and Sub-Saharan Africans.”[ii]

The shift from one population stock to the other came too quickly to have been a change in features that simply occurred or evolved, and happened in too many places over a short span of time to be simple error, so two successive rounds of settlement by two different populations was suggested.

Back in 2005, the authors were quick to point out their theory did not require transoceanic migration, as the earlier group was present in Eastern Asia and could have migrated up and over to North America using the Bering Land Bridge.[iii]

They also argued their theory did not — necessarily — require pre-Clovis settlement of the Americas, but admitted that it would help explain the two waves.[iv] That was a little radical at the time, though no longer. The now disproven “Clovis First” theory, then fading, was the idea that a population of hunter gatherers using projectile points of a particular fluted design (Clovis — named for where they were first found in New Mexico[v]) were the first settlers of the Americas around 10,000 B.C. By 2005, discoveries showed settlement in North America had indeed occurred earlier (for more on the battle over “Clovis First,” see the first Re-Learning History article).

In that 2005 study and others, we discovered early American or Paleoamerican populations didn’t match modern Native American populations. The reasons for this are debated, but that the change in the shape of the skull actually took place during the Holocene is not. In fact, “the morphological diversity seen in the continent over time is of the same magnitude as the difference observed between (modern) Australo-Melanesian and East Asian populations.”[vi]

The study published this week showed more peoples were active around that time, at the end of the Pleistocene era and the beginning of the Holocene era, to the north — more than the two population groups seen in the earlier South American study. Each of the four skulls tested and compared came from a different population group. And the later population group found at Lagoa Santa, the ancestors of modern Native Americans, were not found among these four.

In craniofacial morphology studies, skulls are described, mapped in 3D using the physical attributes of different features known as “landmarks”. The full description, the compiled landmarks, then becomes a comparable mathematical model of the skull. This new study compared the four skulls from Quintana Roo with a database created in part by the 2005 study. This is a reference sample of worldwide modern human populations made up of 18 samples, and is, according to the authors, “one of the largest comparative datasets for 3D craniofacial landmarks, and the only one that includes a reference sample from early Americans.” In fact, the early Americans included come from the region of Lagoa Santa, “the largest collection of early Holocene skulls in the Americas.”[vii]

In the current study, the oldest skull, around 13,000 years old, was found at Naharón, and seemed related to the “arctic North American series (Greenland and Alaska), which have been described previously as robust cold adapted populations and quite distinct from Native Americans.”[viii] The authors caution that the remains are fragmentary, meaning fewer landmarks can be used in comparison.

The next oldest remains, found at the site called El Pit I, were also fragmentary. These, surprisingly, showed “stronger morphological affinities with European populations, which is a pattern of association not previously seen between early Americans and (the) reference series.” Though, again, the researchers caution that the comparison is made with incomplete remains.

The other two skulls date from slightly later, from around the beginning of the Holocene 9000 years ago, and are more complete. The one from Los Palmas seems to compare to the early Paleoamericans found at Lagoa Santa. The final skull in the study, found at the Muknal site, is an outlier, and doesn’t match well with anything currently in the database.

These four very different skulls gives us indications of at least four very different looking people of varying heritage living in the same area from about 10,00 to 7000 B.C. Combined with other studies, this shows Mexico has been incredibly diverse across the entire time humans have lived there, from the Ice Age until today.

Unfortunately, with only four specimens, the new study can’t tell us much about the origins of these peoples, but proving the presence of this diversity does contribute to the realization the old models are obsolete. According to the study’s authors, “…We still do not have an accurate picture of the biological diversity in the Americas over time, and until we have a better understanding of this diversity, it will be impossible to create reliable models for the settlement of the Americas.”[ix]

Though the old models claimed similar migration processes occurred across both North and South America, this new knowledge indicates North America was much more diverse than South America. Only a couple of the many peoples found in the North traveled to the South, the previously identified Paleoamericans and the later people of Northern Asian stock who replaced them. And the “abrupt change” that occurred, from one people to another, in South America, need not have happened at all in North America, “and previous models of population replacement or multiple migration waves may only be applicable to South America.”[x]

This new study supports others which have indicated a greater biological diversity in North America. The authors insist “we are still underestimating the degree of biological diversity observed in the continent.”[xi] It may legitimize some contested North American finds, like Kennewick Man, whose morphology does not classify clearly with recent Native Americans, and matches Polynesian and European populations.[xii]

As the authors of the 2005 study cautiously noted their study didn’t necessarily suggest transoceanic migration nor Pre-Clovis settlement, so too here, there is a note of caution in the new one not to imply a direct migration from the morphological matches: “In other words, strong (matches) between El Pit I (or other early North American specimens) with European populations does not imply that there was a migration from Europe to the Americas.” They can prove the existence of the biological diversity, but insist “it is not enough to establish ancestor-descendent relationships between reference series and the specimens analyzed.”[xiii] In other words, North America was much more diverse than previously thought, but we cannot yet say with any certainty why that was the case.

There is too much to learn — we cannot yet construct viable models. “Until there is a reliable understanding of the biological diversity in the continent, broad spectrum models will always fall short in explaining the origins of Native American populations,” the new study points out. The authors caution other researchers not to build broad spectrum models “based on evidence from only a few regions in the continent,” and they emphasized the need for the “continuous pursuit of new archaeological evidence of early populations in areas understudied in the continent.”[xiv]

The more we learn, the more we realize there is much more yet to discover. The objects of this new study, these four skulls, according to Hubbe et al, “represent now one of the best human remains collections known from the Pleistocene/Holocene boundary in North America.” And they come from four very different peoples, which doesn’t “fit easily in our current models of human occupation of the continent.”[xv]

It was Albert Einstein who famously said, “The more I learn, the more I realize how much I don’t know.” While not willing to draw new conclusions about the origins of the diversity, this new study adds to our understanding of what we didn’t know — that the human populations of the North American continent were more biologically diverse than previously understood. Thus forcing the question — where did they come from? Diverse populations suggest diverse points of origin, which also infers diverse transportation and migration modes. We just don’t know from where, yet, nor how, not really.

But these results are certainly intriguing. And we do know now that our concepts of the migration of Northeast Asians walking across the Bering Land Bridge at the end of the last Ice Age are far too simplistic to explain a North American continent growing increasingly more complex in its apparently diverse populations as the result of new discoveries.

We’re beginning to know what we don’t know.

We’re re-learning history…

Mike Luoma is a writer and researcher from Vermont — find out more at http://MikeLuoma.com.

[i] Ancient skulls tell new story about our first settlers: Early North Americans much more diverse than previously believed, by Jeff Grabmeier, Ohio State News. January 29, 2020. https://news.osu.edu/ancient-skulls-tell-new-story-about-our-first-settlers.

[ii] Cranial morphology of early Americans from Lagoa Santa, Brazil: Implications for the settlement of the New World, by Walter A. Neves and Mark Hubbe. Edited by Richard G. Klein, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, and approved October 28, 2005 (received for review August 18, 2005) PNAS December 20, 2005 102 (51) 18309–18314; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0507185102.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clovis_point.

[vi] Cranial Morphology (2005), as above.

[vii] Morphological variation (2020), as above.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Ibid.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Ibid.