Previously Overlooked, Possible Megalithic Site in Pennsylvania

Did Ancient Hands Shift Boulders and Stones at Bilger’s Rocks?

Did Ancient Hands Shift Boulders and Stones at Bilger’s Rocks?

There may be more to Bilger’s Rocks than people know.

Of course, many people don’t even know of Bilger’s Rocks.

I discovered Bilger’s Rocks, a Rock City in Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, northeast of Pittsburgh, almost by accident, when searching for a summer road-trip stop between a Ceremonial Stone Landscape in Lewis Hollow at Overlook Mountain in New York’s Catskills, and Serpent Mound in South-central Ohio. According to some online sources, it’s evidently known as “Pennsylvania’s Best Rock Outcropping.”

Reading up on Bilger’s Rocks prior to my visit made me curious enough to want to stop, but I wasn’t sure quite what to expect from the place. It turned out to be a fascinating space!

Though Bilger’s Rocks aspires to be no more than a family-centric tourist attraction, I believe there may be evidence of ancient, megalithic work here.

These stacks and groupings are all said to be natural. But glaciers didn’t reach this far south — these boulders are said to be piled up as a result of 300,000,000 year-old mountain-slides, the huge stones tumbling down as Pangaea fell apart, and over time since then. But is that all we see at work?

That natural process may have delivered the boulders here, but I think we see later, human-created stacking, shaping and sculpting of the stones. It’s hard to be sure, as the stones also bear the crude marks of centuries of graffiti. And some truly ancient markings from the sea floor vegetation trapped in the stone’s creation.

Bilger’s Rocks is a privately owned park open to the public, run by the private, nonprofit Bilger’s Rocks Association Inc. They bought and have worked to preserve the site since the 1990s.

Geologists call it a Rock City or Boulder Garden. These are megalithic sandstone formations. Huge stones piled on top of each other. There are also many niches, shelters, caves, slot caves and crevices, hideaways and tunnels among the stones. Climbing is encouraged.

Bilger’s Rocks is a tourist attraction, a forest recreational area. As the sign says, it’s A Place Where Everyone Can Explore. The sign also tells us the rocks are over 300 million years old. These huge sandstone boulders are said to be part of a 300 million years long, gradual mountain-slide of mammoth stones, 20 to 25 feet thick Homewood Sandstone member rocks of the Pottsville Formation, broken apart by frost wedging.

“Constructed by the natural rock and roll of mountain boulders gradually separating and drifting down the Bloom Township hillside,” according to Holly Shok at the Pennsylvania Center For The Book (http://pabook2.libraries.psu.edu/palitmap/BilgersRocks.html).

But a wander around these boulders made me wonder what to make of that idea, that these stacks and arrangements are simply naturally occurring, and reminded me that, in New England, we’d be told glaciers stacked these stones. I double-checked to be certain — glaciers didn’t reach this far South.

An indigenous presence is granted here, all the way back to Paleoindians at the end of the last Ice Age.

Indigenous Americans were said to use the spaces among the stones for shelter. But what if indigenous peoples did more than that? Could they have perched and arranged some of these stones? Shaped or carved into them?

It is hard to tell — this site is just about the opposite of undisturbed. It’s been heavily tampered with and altered. Those preserving the place now are only the latest fighters in a centuries long battle against graffiti. Carved, scratched, and, these days, spray painted human markings can be found in various media all over the stones.

Including the most elaborate: “THE WORLD IS LOOKING TO US — 1921 — JWL”. Chiseled in, complete with a globe of the Western Hemisphere.

Folks have been leaving their marks here for ages. It’s likely indigenous folks did too. Though obscured by later defacing there are places where possible indigenous work appears to lie beneath, flowing with and incorporating the lines of the stones. Sometimes embellishing the traces of ancient sea floor vegetation which left their own marks upon the sandstone.

Many boulders appear worked — even shaped.

On close inspection many of the groupings of stones seemed planned and piled up, as opposed to occurring naturally, when boulders drifted down a hillside. They may have drifted here, but they may have had some help in their arrangement.

Did Native Americans work with stone?

They did when there was stone to work with. Take the Pueblo or Hopi of the southwest for example.

Archaeologists once assumed that, unlike indigenous people the rest of the world over, Native Americans in the northeast never built with stone. While some still hold this to be the case, a new consensus is growing among tribal representatives, amateurs, antiquarians, and some archaeologists, recognizing that indigenous peoples in northeastern North America did indeed work with stone.

In fact, some old stonework assumed to be colonial is now thought to be much, much older, of indigenous origin, and potentially part of ancient, sacred Ceremonial Stone Landscapes.

There seems to be some of that here, including a possible modified rockshelter.

James Mavor and Byron Dix’s groundbreaking 1989 book Manitou helped begin this shift in opinion, making a strong case for indigenous stonework in northeastern North America. Their focus was on New England. More recent work has expanded the area under consideration up and down the eastern seaboard, as detailed by archaeologist Curtis Hoffman and his 2018 study Stone Prayers. Hoffman included Pennsylvania in his book, though the sites covered were further east.

It’s curious to find this modified rock shelter still somewhat intact in such a heavily trafficked place. Maybe it’s because the added stones help make the inside of this cave open on two sides a bit more sheltered.

Though no longer neatly stacked the stones are still here. For how long now? Hundreds of years? Thousands? And how much more of all we see around us here is the work of their hands? Could they have perched and arranged some of these stones?

To my eyes too much here seems repeated, even planned, to be simply coincidence.

There are stones which look like wing and fin shapes I’ve seen before in the northeast as part of possible large scale great serpent stonework.

And there’s more.

Towards the back of the site among smaller groups of stones, this curious assemblage looks an awful lot like an altar of some kind. I began calling it the “Turtle Altar” in my mind, as the boulder projecting out on the left side seemed to look a bit like the head of a turtle.

This could just be a natural stacking of stones which occurred randomly overtime, but it sure looks like someone once put it together.

Could nature be given too much credit? And not enough be given to the ingenuity and creativity of indigenous peoples? Not enough credit given to their urge to celebrate and use amazing spaces?

Are we biased against believing indigenous Americans did anything?

The myth of a pristine wilderness in North America prior to European arrival — populated by only a few Native Americans living lightly off the land — was propagated in the 18th through the 20th centuries. And this informed much of what was said to have occurred naturally in the so-called “New World” — a name which reinforces this myth.

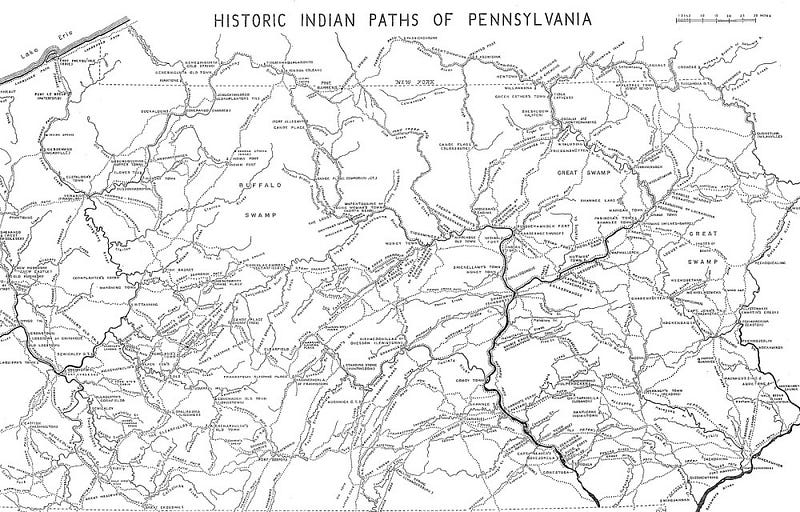

But it’s not true. There was no pristine wilderness — millions of people lived here. As historian Scott Weidensaul points out in The First Frontier (2012), “there was no wilderness, at least not in the sense of land unoccupied and unaltered by humans.” Early reports of North America tell of wide-open treeless areas and tended, curated forests. And far from being trackless this land was crisscrossed by trails and “footpaths linking every corner of the continent.”

The Europeans didn’t understand but reported on Native Americans using fire deliberately. And we know now these controlled fires helped maintain underbrush scrub growth and manage foraging bushes for wildlife. Abundant wildlife and edible plants were reported by early explorers and traders, including many square miles of open cornfields in what is now New York.

There were millions of people here for over 10,000 years — there was no wilderness. Not until new people showed up, gave things new names, and decided that this was their New World.

Bilger’s Rocks is named for Jacob Bilger the German immigrant who first settled here. We don’t know what it was called before that.

But we do know German settlers equated some Native American spirits with Satan and called places sacred to them “Devil” This and “Devil” That. And here at Bilger’s Rocks some spaces have been nicknamed The Devil’s Kitchen, The Devil’s Dining Room, and The Devil’s Dungeon, some of which can only be reached by edging through narrow crevices between boulders.

These devilish names, and the modified rockshelter, add to the possibility these rocks were once part of a Ceremonial Stone Landscape used by Native Americans. And we do know that nearby Clearfield used to be a major Native American village named Chinklacamoose on the major Native American trail known as The Great Shamokin Path.

It turns out, on its way westward out of Chinklacamoose, The Great Shamokin Path ran right past Bilger’s Rocks. Greenville Pike — the road you take up to Bilger’s Rocks Rd — was once part of The Great Shamokin Path.

Those paths became settlers’ trails, and then our roads. A part of our Interstate 80 roughly follows the route of The Great Shamokin Path. So, while we’re now in out-of-the-way west-central Pennsylvania, long ago Bilger’s Rocks was right next to a major thoroughfare.

Once we know about the proximity to that path, the heavy traffic here makes a bit more sense.

As impressive as these boulders are — as amazing as this space is — and even though there is evidence piling up in favor of indigenous American stonework here, the sheer amount of casual damage done over the years by vandals and artists, renders the possibility of determining the provenance of the work somewhat moot.

All the same, I’m glad to have found Bilger’s Rocks on my way from Lewis Hollow to Serpent Mound.

And I wondered, after discovering the old Native American trail The Great Shamokin Path ran through here —

Did indigenous folks perhaps follow this same route, long, long ago?

Want to see more of Bilger’s Rocks in Grampian, Pennsylvania? Check out my mini-doc on Bilger’s Rocks on YouTube: https://youtu.be/dGybBmnocyg.