Burlington, Vermont’s Hidden Gem Reveals Wonders

Unique Natural History. Notable American History. Fascinating Geology. Exotic Botany. Archaeology. Spirituality. Take-your-breath-away vistas of Lake Champlain and the Adirondack Mountains…

Your experience of Lone Rock Point peninsula in Burlington, Vermont has the potential to be as immersive as you desire, whatever stirs your curiosity.

There is much to take in on this 130 acre promontory on the north end of Burlington’s waterfront, even if your only goal is to get away somewhere peaceful and beautiful.

I’ve been searching out amazing spaces around our city and state—getting me out of the house in this pandemic year, and helping me find gems like Lone Rock Point hiding in plain sight, right inside Burlington’s city limits. I like sharing the experience, hopefully helping everyone escape a little bit, even if only vicariously.

Lone Rock Point is privately owned by the Episcopal Church of Burlington. Luckily, they have public hiking trails — you apply for a day pass online, get a quick email of it to keep on your phone, and you’re off. Unfortunately, that means there are some areas off-limits to the public, but they do share most of the peninsula on the Rock Point Trails.

Lone Rock Point is geologically famous for the exposed Champlain Thrust Fault. The Thrust Fault is the exposed rock you see looking at the Northwest side of the peninsula, the large chunk of gnarled and crinkly tan-orange and gray rock hanging above a line of plain gray stone below.

The fault itself runs from Quebec, Canada down to the Catskills Plateau, almost 200 miles. On this peninsula, it’s at eye level. Although, when I ventured out in mid-March, the stone steps down to the beach in front of the thrust were covered by thick ice and flowing meltwater, so I wasn’t able to get up close and personal.

A little geology — there’s a beautiful tan rock seen all over Burlington, what they call Lower Cambrian Dunham Dolostone, and it’s about 500 million years old. At the thrust fault, the dolostone sits on top, making the dolostone the “hanging wall”. The dark gray Middle Ordovician Iberville Shale below is the “footwall”. It’s about 460 million years old, 40 million years younger than the dolostone.

Older rock is usually found below younger rock. But 10 million years after the shale was created, a land form including what’s now New Hampshire and Maine came slamming into Vermont, pushing up the Green Mountains in the Taconic Orogeny.

In that process, the layer of dolostone was pushed up and over the shale, all along this fault, from Canada down to the Catskills. Since this reverses the usual order of older rock below younger, it’s called a Reverse Fault. As it’s at a low angle to the Earth’s surface, it’s then known as a Thrust Fault.

And now, you know.

The peninsula seems to have been open land until purchased by Burlington’s first Episcopal Bishop (and noted polymath) John Henry Hopkins in 1841. His family eventually bequeathed the peninsula to the Church. Hopkins was a noted oil and watercolor artist and an esteemed architect — he literally wrote the book on Gothic Architecture, and was responsible for introducing it to the United States. Hopkins built his family’s home on a hill on the site. He then constructed a boy’s school, in the Gothic style.

John Henry Hopkins Jr., himself noteworthy for writing “We Three Kings of Orient Are”, also wrote a biography of his famous father, and told of how stone blocks for the building were quarried on site — the ruins of the small quarry still sit nearby in what is now Burlington’s Arms Forest , on the other side of the Burlington Bike Path.

John Jr. noted that economics dictated that only the foundation was built with the quarried stones; the rest was brick. They didn’t have the money to quarry it all. Over time, the building came to be owned by the Vermont Episcopal Institute, until it burned to the ground in 1979.

It is curious that a religious organization now owns Lone Rock Point, as it was likely a holy and sacred place going back thousands of years. As the Univeristy of Vermont’s Burlington Geographic notes:

“Rock Point’s lake front location makes it a likely location for Native American activities. Archaeologists believe that the Rock Point site is of “high prehistoric sensitivity” meaning this area was probably used by the Abenaki for a wide variety of activities. According to the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation, chert projectile points were found along North Beach just south of Rock Point.”

The Rock Point Trails head out onto Burlington’s North Beach for a short stretch before turning back up onto the peninsula proper.

What were those “Native American activities”? Archaeologists disagree over Northeastern Native Americans’ ritual use of stone in Ceremonial Stone Landscapes — constructing sacred spaces, cairns, stone rows and effigies using stone. My research, however, has led me towards agreement with past president of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society Dr. Curtiss Hoffman, of Bridgewater State University.

In his Stone Prayers (2018), Dr. Hoffman offers “quantitative support for the indigenous construction hypothesis” — as opposed to other archaeologists who suggest the stone works are all colonial, or amateur sleuths who believe they were built by pre-Columbian European explorers — based on an objective scientific analysis of over 5,550 sites in the Northeast and along the Eastern seaboard.

Here in the Champlain Valley, it’s likely Abenaki ancestors used stone to express themselves. I’ve found a few interesting stone sites in my explorations and investigations. Dr. Hoffman continues to maintain an inventory of sites, and I’ve reported suspected ones to him for his inventory.

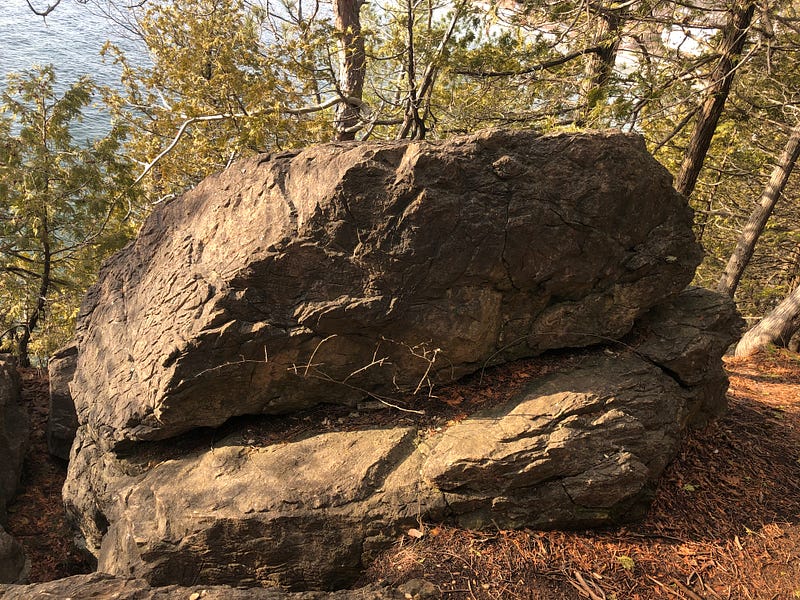

The most prominent possible Native American stone work on Lone Rock Point, to my eyes, is the row of boulders atop the northwestern ridgetop just west of the thrust fault, but there are many other possible candidates, large and small.

We see a boulder whose shape has been helped into a potential bird effigy form, boulders added to ridgeside bedrock to form wing-fins, serpentine ridge rock carving, and many more creatively placed stones and stone assemblages.

Again, this is all speculative, preliminary and theoretical. And you don’t need to believe any of it to enjoy yourself at Rock Point — but why not keep your eyes open? What do you see in the stones?

Vegetation on the peninsula suggests this may have been a sacred place for ancient Abenaki as well.

Out on the point, there are cedars and pines, which were important to medicine keepers among Native Americans.

This old calcium-rich dolostone creates a unique soil feeding these trees and this vegetation, which, according to Burlington Geographic:

…Allows for a unique set of plants to take root. Along the edge of the Rock Point peninsula, the Limestone Bluff Cedar-Pine Forest is the dominant community, with northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis) being the most common tree, along with white and red pines… …cool air from the lakeside creates a moist microclimate in which some rare herbaceous plants grow, such as walking fern (Asplenium rhizophyllum) and purple clematis (Clematis occidentalis). (Additionally, there are)… maidenhair ferns (Adiantum pedatum), basswood trees (Tilia americana), and herbaceous plants like Dutchman’s breeches (Dicentra cucullaria), large-flowered trillium (Trillium grandiflorum), hepatica (Hepatica acutiloba), wild ginger (Asarum canadense), and meadow rue (Thalictrum diocicum).

Laying down a little botanical science on Lone Rock Point.

The two or so miles of trails at Rock Point are fairly easy for any experienced hiker. There are more challenging opportunities for experienced rock climbers as well. There is even one universal access path which is accessible for everyone to use to get onto the peninsula and up to the Outdoor Chapel.

The trails were refurbished last year as the Episcopal Church joined with the City and Lake Champlain Land Trust to preserve the space and maintain these public trails on this private property. As mentioned above, Rock Point asks visitors to register for a free Day Property Pass before hiking, which is easily obtained through their site: https://www.rockpointvt.org/trails.

Inland to the east, just across the Burlington Bike Path, an old railbed along the waterfront that divides the Lone Rock Point peninsula from the mainland, the Rock Point trails connect up with the many paths of Burlington’s Arms Forest, another wooded gem tucked away in the middle of the city, with an additional 30 acres of woodlands and more opportunities for wandering Burlington’s “urban wilds”.

The Lone Rock Point peninsula is one of those places nearby which, when I wander into them, remind me why I live in this sometimes magical place we call Vermont.