Possible Repercussions From a 19th Century Clergyman’s Folly

Did desecration doom two schools? Do we still experience negative reverberations from a 19th century Christian clergyman’s destruction of a possible sacred stone site?

Visiting Arms Forest and Lone Rock Point peninsula in Burlington, Vermont, this spring, I was pleasantly surprised to discover possible Native American stonework in these side-by-side parks, one public and one private but open to the public, near the Lake Champlain waterfront.

In Arms Forest, but nearly on the border between the two parks, we also find an old quarry. Based on my observations, research, and intuition, I have a growing sense and impression that this quarry was cut into something else, something older.

Perhaps even something sacred.

In assessing the stonework found on multiple visits to Arms Forest — standing stones, possible terracing, potential prayer seats and effigy stones, even possible large-scale great serpent stonework — I began to suspect this old quarry could have once been a sort of processional space coming up off the lake, as this quarry lays at the head of a ravine, a natural path rising up out of Eagle Bay.

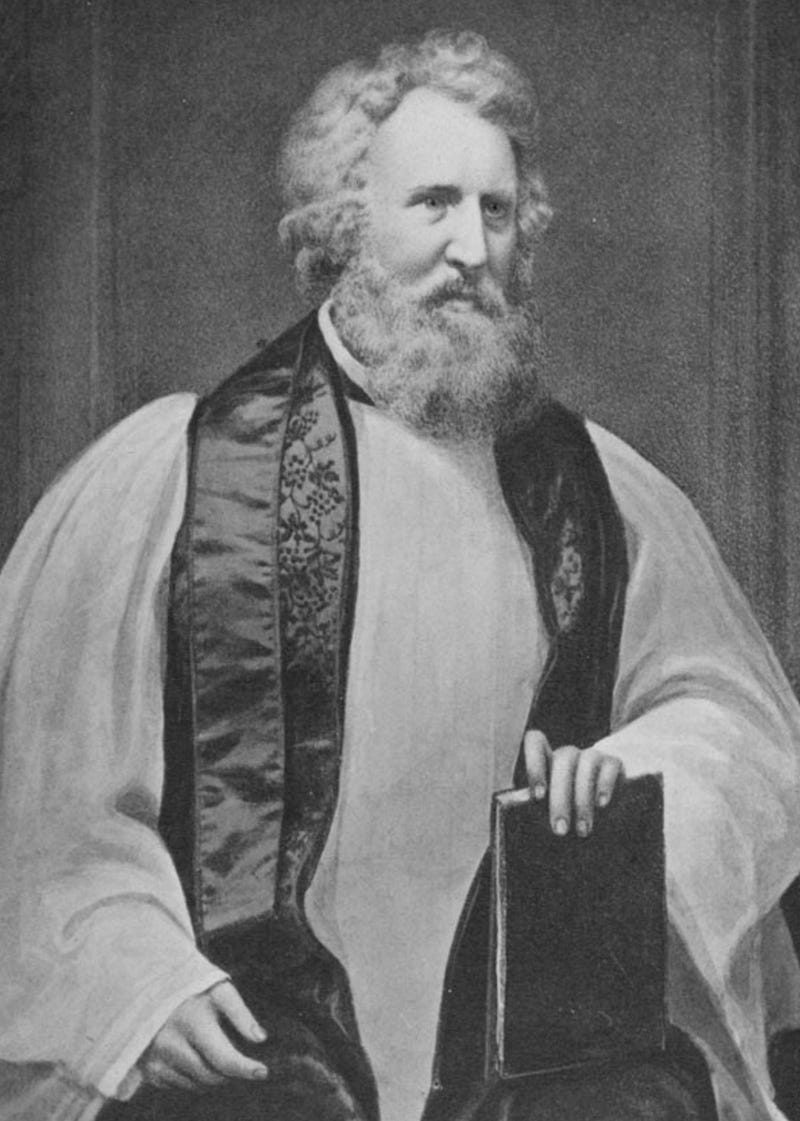

Expanding my investigation out onto the Lone Rock Point peninsula brought more curious stonework into view, and also introduced me to the man who first bought and settled “Rock Point” in the mid-1800's, the Reverend John Henry Hopkins. He’s been in the news recently, as students at the Rock Point School voted to have his portrait moved to a less public place, after discovering he had offered a biblical justification for slavery during the civil war.

In addition to his priestly vocation, he was also an artist — a painter, watercolorist. And an architect, who helped introduce Gothic architecture to the United States. He was also Burlington, Vermont’s first Episcopal Bishop.

He and his family settled Rock Point, filling in hollows, and dynamiting some of the ledges to level the land, and make it usable. His family later gave the peninsula and the land to the Episcopal Church, who own it today. They partner with the city and others to keep the place open to the public for recreation.

Speaking of Hopkin’s family, the Bishop’s son, John Henry Hopkins Jr., is noteworthy for composing the Christmas hymn We Three Kings. He also wrote a biography of his father (The Life Of The Late Right Reverend John Henry Hopkins, First Bishop Of Vermont, And Seventh Presiding Bishop — F. J. Huntington 1873), which in part chronicles their time on the peninsula — one chapter is even titled “Rock Point”.

But it’s in a later chapter where I found this quarry.

Online guides to the Arms Forest say stone from this quarry could have been used to build the nearby Ethan Allen Tower, built in the early 1900’s.

One mentioned a brief commercial usage of the site in the 19th century.

Another suggested that Bishop Hopkins may indeed have used it, as his son’s biography speaks of them quarrying stone for the foundation of an institute built on the peninsula in that earlier chapter on Rock Point.

All of these are, I believe, incorrect assumptions.

This quarry is actually on old Rock Point property, on the old church farm. In a later chapter, Junior seems to describe it quite specifically:

“During the last year of my father’s life (1868), he set the quarrymen to work and quarried out a large quantity of stone near a site on the church farm where he had finally determined to place the girls school… But he never saw even the cornerstone laid, and the quarried heaps have slept undisturbed since his departure.”

That was published in 1873, and still seems to describe this site to a tee.

Something more brought the destruction into our time. After that first visit to the Lone Rock Point peninsula, I headed out back through the more familiar Arms Forest, past the quarry. It was getting dark, but I noticed something I hadn’t before — as I walked down the driveway of the now-closed Burlington High School, it appeared they had sheared a mound in half to build the driveway. And this mound was just above the quarry!

It was too dark to see much, but I peeked around.

What I saw made me come back when I could, the next day. In the dimming twilight and shadows, it looked like impressive stonework could be there.

Unfortunately, when I returned the next day, there atop the quarry I found what looked like more destruction. Not only had they sheared the mound in half, they seemed to have bulldozed it a bit as well. Shoved stuff around, some.

There were still shaped stones scattered all around — possible wing-effigy forms, as if there were some sort of wing-adorned platform here, perhaps at the end of the processional way.

As I surveyed the destruction — the possible destruction — I couldn’t help but notice we were right next to the Tech Center at the Burlington High School, where they’d first discovered toxic PCBs had been used in the building’s construction back in 1964 and were now leeching out. This eventually turned the whole site toxic, forcing them to close and then condemn the school building.

You might have heard about it on the news — they converted the old former Macy’s site downtown into the new temporary Burlington High School. The old building will be torn down. It’s not salvageable — condemned. It’s doomed.

And, as we learned from the biography, the girls’ school the quarry was originally cut for was never even built — Hopkins’ death was its doom.

That’s two doomed schools, right next to this quarry.

That’s the speculative journey my mind took off on as I surveyed what seemed to be a destroyed sacred space. Of course, this could just be a string of coincidences I’m tying together.

And why would there be negative reverberations, anyway?

Because…

I believe Bishop Hopkins destroyed this space deliberately.

And? As a result? The disharmony and imbalance created doomed his girls’ school, and now — seven generations later — has closed Burlington High School.

Hopkins was an artist and architect. As an investigator of stone sites, my own artistic background, work in masonry construction, and understanding of spatial relationships, among other things, helps me see stone sites others may have missed.

As a landscape painter and an architect, I find it all but impossible to believe Hopkins didn’t have a similar eye for such work. Also? As a noted clergyman of his day, he may have seen it as his duty to quietly destroy anything he found that looked like a Native American holy site, as the limited understanding of his day saw the “savages” as “devil worshippers.”

This didn’t occur in isolation. Several stone sites I’ve visited contained examples of what appeared to be stone work deliberately marred or destroyed. My conclusion is that settlers often destroyed anything on “their land” that looked “off” to them, or which they thought was “devil’s work”.

The quarry sits there, still, one such possible example, with its many quarried but unused stones still sitting beside it, their sleep yet undisturbed. But what disturbances did they cause?

Native Americans speak of Ceremonial Stone Landscapes in Northeastern North America comprised of stone prayers, stone constructions on the land. They tell us these were built to bring balance.

At the very least, even innocently demolishing such a site could bring imbalance, and disharmony.

Doom?

Idle conjecture? Perhaps. Sometimes, what I do is more intuitive than scientific, and this assessment is — admittedly — one of those cases, stemming from an increasing sense of wrongness emanating from observations of the quarry, the area around it and the hillside above it, along with the incredible coincidence of two doomed schools having been located next to the site.

As an investigator and researcher, when I see the shape of a question like this, I want to ask it, even if I’m not yet equipped to offer any solid answers. Ask the question, offer some ideas, and let the conversation begin.