“Redemption Rock” — A Reminder of Forgotten History

A little history, a little mystery, and a whole lot of ice…

Just off Route 140 in Princeton, Massachusetts sits a massive ledge with a short paragraph carved into one side. Folks pass by it often as they use the popular Midstate Trail, which runs by the rock. Some may stop to read its chiseled-in words, but not all. Those who use the trail often tend to run, walk or bike right past. Even those who stop to read the words may not give them too much thought:

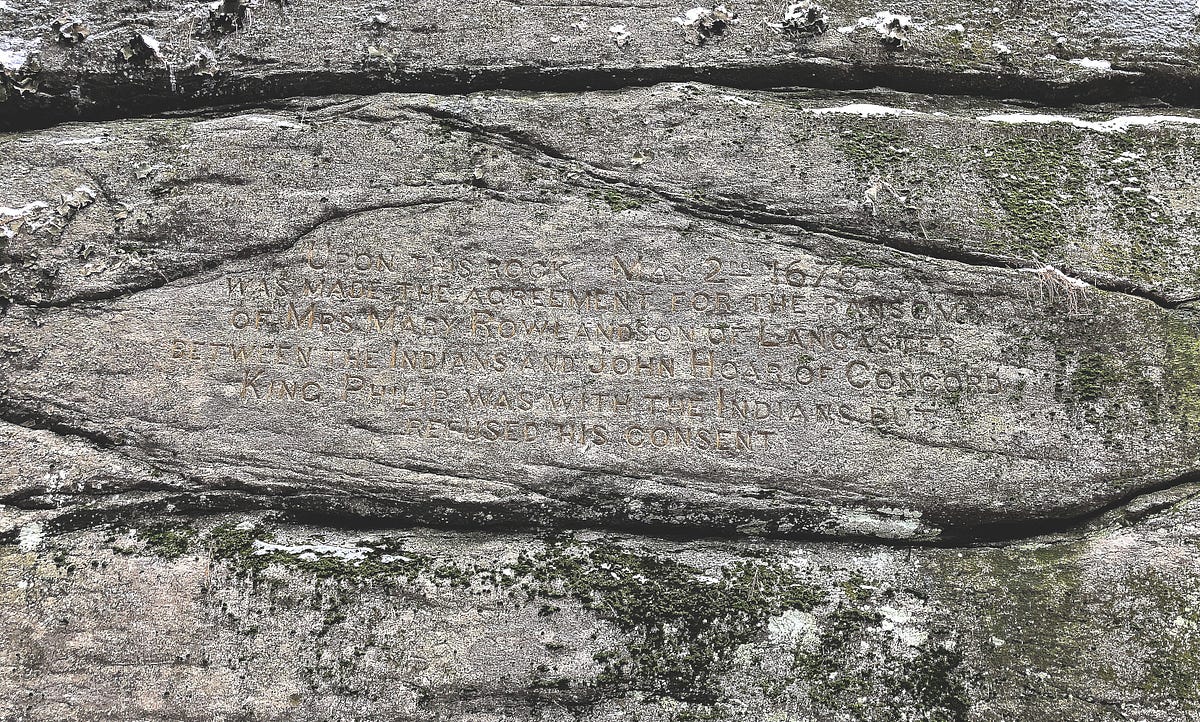

Upon this Rock May 2nd 1676 was made the agreement for the ransom of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson of Lancaster between the Indians and John Hoar of Concord. King Phillip was with the Indians but refused his consent.

King Philip? Indians? Don’t hear too much about them these days. Who was Philip, again? Some sort of rogue king?

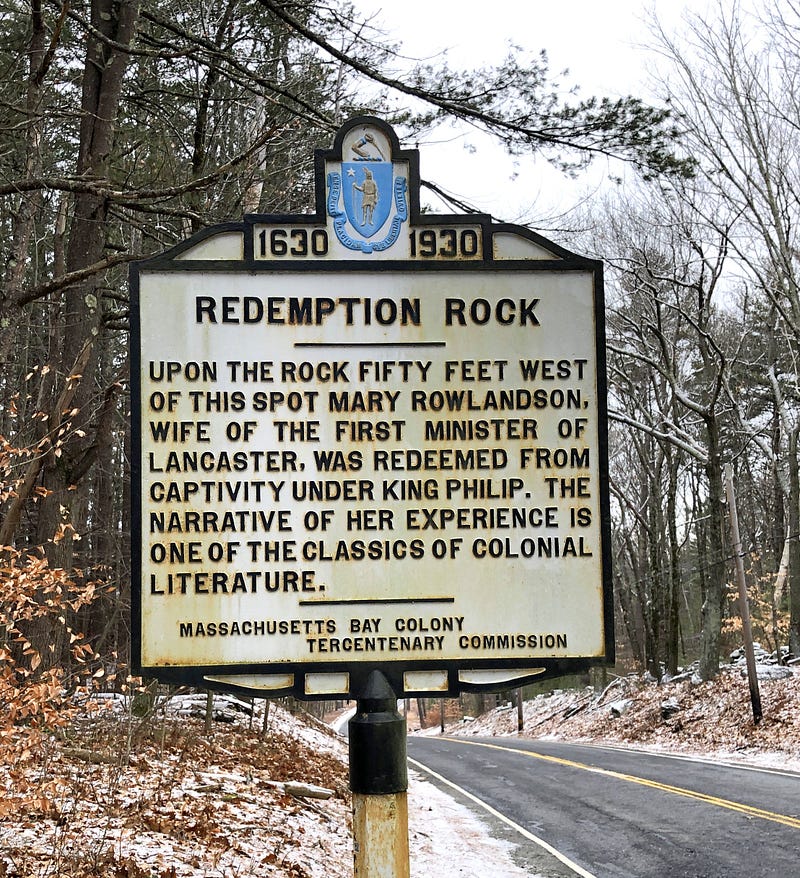

A highway-side Historic Marker also relates part of the tale:

“Upon the rock fifty feet west of this spot Mary Rowlandson, Wife of the First Minister of Lancaster, was Redeemed from Captivity under King Philip. The Narrative of her experience is one of the classics of Colonial Literature.”

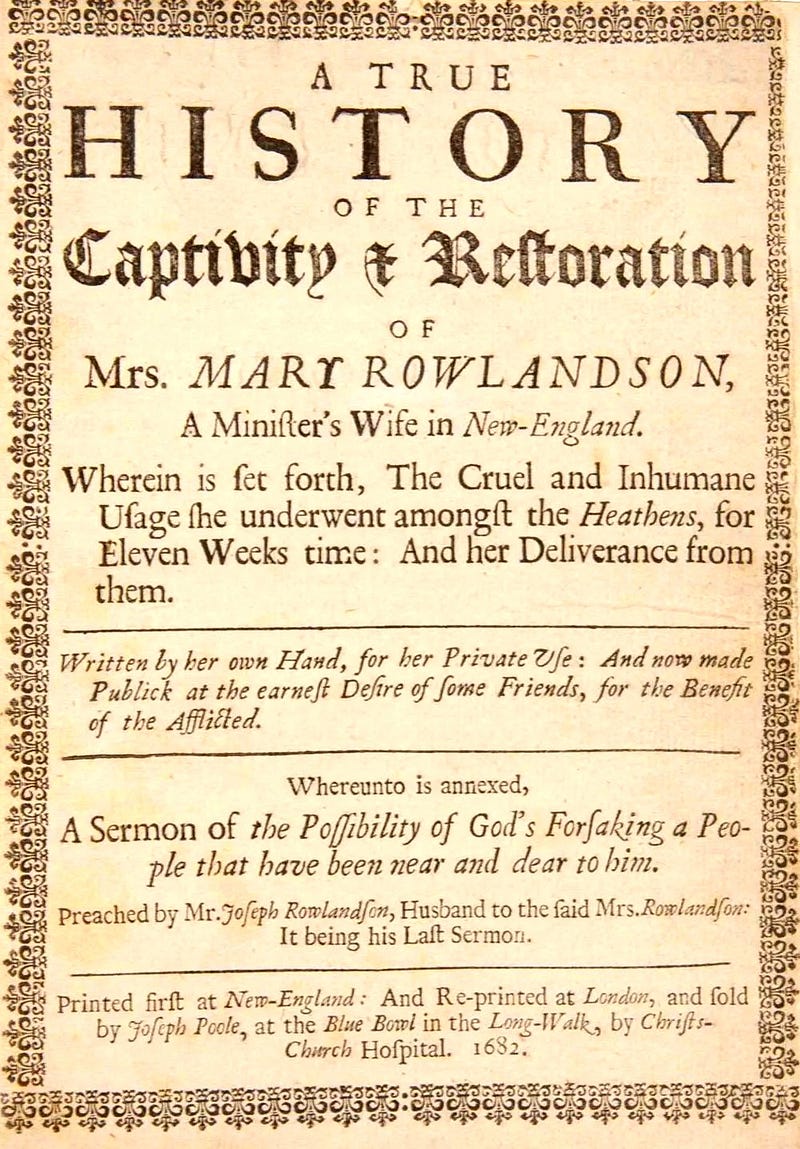

The former captive, Mary Rowlandson, did indeed later write a book about her captivity, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God: Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, which went on to become the equivalent of a 17th century bestseller, though forgotten, now.

I headed to Princeton and Redemption Rock to see the landmark stone and also because I’d heard there was a rockshelter nearby. Instead of a rockshelter, I found a stone chamber in the vicinity, on the other side of what appeared to be a constructed stone waterway, seemingly designed to keep water from flowing into the chamber on its way to a beaver pond just beyond.

A Christmas Day ice storm had coated everything in a glistening, slippery, hard shell. Two days later, as I carefully walked around the Princeton woods, it was still slippery going. The weather on this trip had been proving a little challenging for exploring.

A few days earlier, I’d braved frigid wind chills to check out King Philip’s Rock in Berlin, Massachusetts, a huge 15' by 25' boulder on a hill just south of Gates Pond, said to be a meeting place for King Philip and his warriors before and after raids on Lancaster and Marlborough. Berlin was once part of Lancaster.

Rock of King

Glacial Erratic? Perched Boulder? Shaped Stone? Searching Out King Philip Rock in Berlin, Massachusettsglowinthedarkradio.medium.com

So who was King Philip? And what’s with the rocks?

They’re from a somewhat darker chapter of our American History which seems to get glossed over. Popular histories often skip from the Pilgrims’ landing in 1620 to the Boston Massacre and beginnings of the American Revolution in 1770. But — obviously — a lot went on in the 150 years in between.

Including the bloodiest war ever on North American soil.

In the 1670's, rural Princeton was the rugged western frontier for the first British Colonies in the Northeast of what would become North America, just beyond the frontier colony town of Lancaster (formerly Nashaway). The sons of the original settlers of Massachusetts Bay Colony and their families, along with new arrivals, had been pushing further and further inland from Boston and its more immediate surroundings, buying, negotiating for, and claiming, land from its Indigenous Peoples.

In 1675, some of the Indigenous Peoples of the area began resisting and fighting back against the expansion.

Metacom, a Wampanoag Satchem originally based near Plymouth Colony, was called “Philip” by the Europeans. Metacom was the son of Massassoit, who had welcomed and helped the Pilgrims upon their first landing. But relations soured as the colonies expanded their territories and told the Indigenous Peoples they were no longer sovereign but subject to British Law and the Crown.

In mid-1675, the Colonists pinned a murder charge on Metacom and moved militarily to take him into custody. Metacom not only rejected his guilt in the charges, he rejected their right to be brought against him. He had earlier refused to disarm. He and his people went on the run, and the Colonial forces began trying to hunt them down.

As Metacom and his people evaded their grasp, other Indigenous warriors began striking frontier targets. Towns and outposts were raided. As tactics escalated and casualties increased skirmish by skirmish, the conflict devolved into an all-out war, now known as King Philip’s War — a war which raged so out-of-hand some historians do indeed call it the bloodiest conflict ever fought on this soil.

In a pre-emptive December attack on the Narragansett — who had not yet joined in the war, but had harbored folks loyal to Metacom — Colonial forces didn’t stop with the warriors, going on to kill at least a thousand Indigenous elderly, women and children non-combatants while completely destroying winter homes and wigwams so any survivors were left homeless in the ruins.

Some suggest prominent Colonial women such as Rowlandson were taken captive in order to prevent such tactics, in hopes that Indigenous women would be safer in proximity to captured Colonial women, and Rowlandson did travel for a time with Weetamoo, a prominent Wampanoag leader and kinswoman to Metacom.

Indigenous Warriors inflicted their own death toll in raids and skirmishes. 14 men died in the early February raid on Lancaster, when a combined force of hundreds of Wampanoag, Nipmuc and Narragansett took over the town — and Mary Rowlandson was taken captive.

We know something of her captivity because of her later narrative. After being “removed” several times to spots slightly further west over the next couple of months, Rowlandson was eventually returned to Wachusett, where King Philip was camped, about a mile away from Redemption Rock. Her release was then negotiated and secured, and finalized here at Redemption Rock in early May.

Mary Rowlandson was freed at Redemption Rock, and went on to write her famous book. The war did not end as well for King Philip and the Indigenous Peoples of Southern New England.

On August 12th, 1676, Metacom was shot and killed. His corpse was then desecrated and dismembered, his severed head placed on a prominent pike near the entrance to Plymouth for the next few years.

Captured Indigenous Peoples were sold as slaves and sent off to Barbados, never to see their homes again. Some displaced Indigenous folks sought out new homes and new relations further north and west.

The war didn’t really end with the death of Metacom in 1676, although that was the traditional dating. Battles on the northern front continued until 1678 — and up there, the Indigenous folks won.

And in a larger sense, Indigenous resistance and warfare continued into and through the 18th century, though the Europeans tended to minimize and bracket the conflicts to match up with their continental battles, as the Indigenous opponents were now often allied with the French.

So, King Philip’s War was followed by King William’s War (1688–1697), Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713), Dummer’s War (1722–1725), King George’s War (1744–1748), Father Le Loutre’s War (1749–1755), and the somewhat better-known French and Indian War (1754–1763). To name a few.

Wabanaki forces, allied with the French and based in the north, continued to raid Colonial towns and outposts in the south. And take captives. During Queen Anne’s War, three men were kidnapped just south of Gates Pond, for example. They were carried up to a place near Montreal, and forced to build a mill at Fort Chambly.

So many wars. So much blood. And yet? We don’t hear about those years or those wars very often. They’re not a publicly celebrated nor publicly condemned part of our culture. They’re just — ignored. We jump from the Pilgrims to the Revolution, skipping over a lot of history.

Investigating stone sites has involved some supplemental education in several disciplines, including history, and it’s been eye-opening discovering how extensive the Indigenous presence was around Central Massachusetts.

I’m not only learning history, it’s coming to life around me. And in learning about Indigenous Peoples’ Ceremonial Stone Landscapes, I’ve discovered some of that history is hiding in plain sight, all around.

There’s an emerging realization that the Indigenous Peoples of what is now Northeastern North America worked with stone, and that some of the structures traditionally assumed to be colonial farm leftovers — some stone rows and cairns, for example — are actually much older.

Some are ancient stone prayers, and parts of Ceremonial Stone Landscapes. Ceremonial Stone Landscapes is the term preferred by USET, United Southern and Eastern Tribes, a nonprofit, intertribal organization of Indigenous Peoples, for these ritual stone work sites in eastern North America.

Amateur researchers and antiquarians have been pointing out the possible Indigenous origins of the stone work since the 1980’s. Over time, more and more professional voices have joined the discussion. Even more importantly, Indigenous voices emerged to confirm the hunches of the researchers had been correct.

But consider the “Indian Stones” found around the area. Redemption Rock… King Philip Rock... and many other big boulders bear “Indian Names”, like Sleeping Rock in Berlin. It’s curious how important large stones were to Indigenous Peoples in this area. Several boulders in central Massachusetts are named King Phillip Rock. All are said to be Metacom’s meeting places. I know of at least one in Berlin, one in Sharon, and one in Winchendon, to name three.

Yes. The importance of stone to local Indigenous folks has been this obvious.

As evidenced by Redemption Rock, even in the second generation post-Contact the largest stones were still significant places where Indigenous folks conducted important business treaties and exchanges. Though the English settlers needed to chisel the event into the stone to bear witness, for the local Indigenous folks, the Stone itself bore witness — it was the Witness.

I wanted to observe and really take in Redemption Rock, and see if I could understand what made it such a worthy witness for those events of 1676.

A trip around the stone revealed almost aquatic embellishments. A couple of stones appeared to have been added to resemble wings or fins.

One stone alongside appeared to be worked on top, perhaps another fin, or maybe an attendant porpoise.

Even around the back of the ledge, at its lowest profile, it suggested a long aquatic form — reinforced by the placement of a boulder fin on the top.

These are interesting stone embellishments, and given the preservation of this space, likely both ancient and indigenous.

Redemption Rock appears to be more than just a prominent landmark at which to meet and exchange a hostage. There are subtle embellishments which suggest a reverence going back a very long time. There is a significance to this stone, a certain something about it, though exactly what that is may escape us, today.

There’s something about stone chambers, too. They intrigue so many. Seemingly ancient. Mysterious. Having now seen a few up close and personal, the one general observation I can make is that you can’t generalize about New England’s Stone Chambers. Each one is unique.

There are some similarities, and a careful study would likely reveal a few separate types. Yet, each stone chamber possesses unique characteristics.

This one in Princeton, near Redemption Rock, has the widest front opening I’ve yet seen on a chamber. The stone steps leading down and in are another feature I hadn’t come across before. Can’t recall another associated waterwork like this, either — just some of the chamber’s individualistic features.

How old is it? Hard to tell from just observation.

There are signs of settler usage — the joints between the stones are mortared.

There seems to be a wooden floor or hatch towards the back — I did not clear the leaves away to check for the extent of the flooring but noticed a hollow sound when I stepped to the back of the chamber. A couple of gentle stomps confirmed the flooring and raised a musty, woodsy, and wet-stone scent.

And yet? There are a few signs which suggest a possibly earlier original construction period for this chamber. The walls of the chamber are constructed with odd-sized, large stones laid in irregular courses, not typical of European-influenced chambers, but indicative instead of Indigenous work.

There is a bit of an arch to the walls of the chamber — they bow in just a bit towards the top. This, too, isn’t conclusive, but most colonial and settler chambers appear more squared off and boxlike — with those even courses of stones, or at least courses attempted as such, neither of which we see here.

As a former mason tender looking at the mortaring, to me it appears added post-construction, and not pointed in any real sense, just sort of smeared on and in-between the stones, and obviously not required for the construction of the walls.

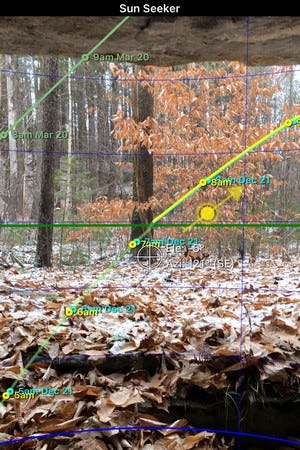

I also found possible solar alignments with the ridge to the east of the chamber.

Looking out from the back of the chamber, there appears to be an Equinox Sunrise alignment to the upper left and a Winter Solstice alignment towards the center — which seems to line up with Redemption Rock itself on the other side of the ridge.

The ridge provides an artificially high horizon line — the sun on these occasions would seem to clear the ridge at approximately 8 AM (I used the Sun Seeker App to check the alignments).

This stone chamber possesses both older and newer elements — a bit of a blended head-scratcher.

The small creek around the chamber is stone-lined and in places obviously constructed — a sort of stone-wall canal routing the water around and away from the chamber.

Some of the stones show obvious tool marks, also indicating likely post-contact construction of the flatter stones on the top of the work.

Exploring and researching stone sites has reinforced the fact there is always more to learn. As with so many subjects, the more you know, the more you realize you don’t know. Recent works in the field of history can help fill in some gaps, and help us learn about and understand these early conflicts.

Recommended: The First Frontier by Scott Weidensaul — a good general survey of the entire pre-American Revolution Colonial period, up and down the east coast of North America.

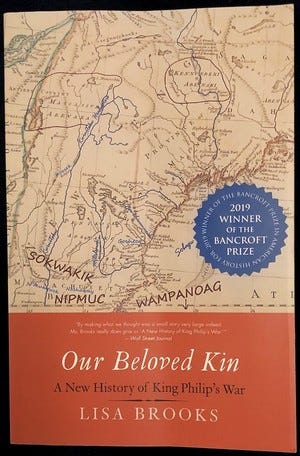

More specific to King Philip’s War: Lisa Brooks’ recent Our Beloved Kin, A New History of King Philip’s War, which seeks to de-colonize the narrative by turning to indigenous sources and other accounts previously overlooked or ignored. A fascinating reconstruction of events on the early frontier, highly recommended.

If the subject intrigues at all, there’s certainly a lot more to learn. A whole lot of history we don’t hear about anymore.

I find taking the time to delve a little into history creates the opportunity for greater resonance and a deeper experience when later exploring. And, ironically, greater knowledge can also help to kindle greater mystery, in knowing what you don’t know.

I know I’m happy I didn’t slip and fall during my visit to Redemption Rock and the nearby Stone Chamber. The icy scene was somewhat surreal, every stone, tree, branch and fallen leaf ice-coated, every step too loud as I gingerly crunched around on top of the glistening crust, pondering a little history and a little mystery. And wondering…

What becomes of a monument when its war is forgotten?