Exploring Stone Chambers in Massachusetts and Vermont

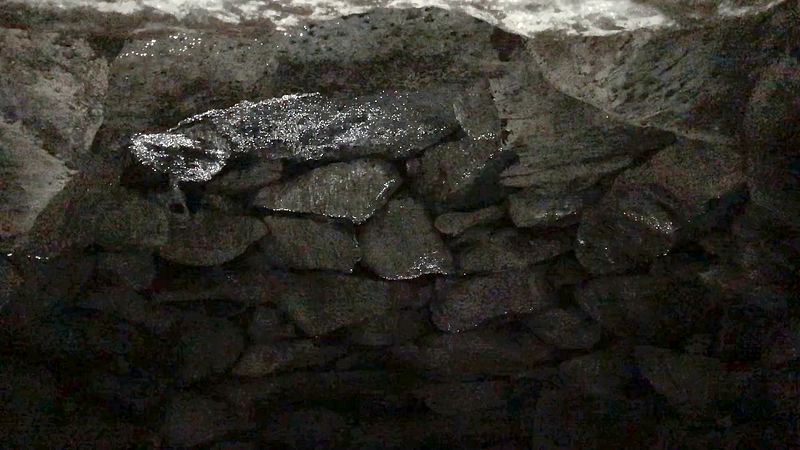

I’m inside the dome-shaped interior of a beehive stone chamber. Optical luminescence dating (OSL) places its time of construction at around 1200 to 1500 AD, 500 to 800 years ago.

This isn’t somewhere in Europe. This is in Upton, Massachusetts.

This stone chamber with its long passageway has inspired much speculation. The stone construction’s resemblance to similar structures found along coastal Northern Europe fueled a great deal of speculation in the 1970’s on the presence of pre-Columbian European explorers. Other researchers detailed stellar alignments they found from inside this chamber using stone points on nearby hills, and made a case for this being a Native American spiritual space and stellar observatory. And there are more theories out there.

As I visit The Upton Stone Chamber, I hold no preconceived ideas. I don’t know what it was, who built it, nor what it had been used for. I don’t yet know much about the Native American stellar alignments. I’m aware of some of the pre-Columbian explorer theories. And, though it gave good directions to sites, I don’t quite trust my guidebook Archaeological Oddities by mainstream archaeologist and skeptic Ken Feder. I found it problematic when he admitted that he rejected the luminescence dating on this site simply because it didn’t “fit” his preconceived ideas, which didn’t seem scientific to me.

I enter the chamber with an open mind, and open myself up to whatever the stones will tell me. And though it may get me accused of trafficking in woo-woo, I will say this — I sense something, a great, non-personal presence, of Something being there, and having been here, for a very long time.

A great, still quietness. Or great, quiet stillness. And yet? Massive. Perhaps benevolent, but more neutral. Watching, maybe waiting? A sense of There, there. Not seeking to be acknowledged, but acknowledging, if sought out. Almost nothing, but also almost everything. Age. If nothing else, a sense of great age hits me in this space. Profound in the moment, it’s difficult to relate the full impact in words.

Intellectual curiosity led me to seek out the chamber. But the experience’s impact is more visceral, my response intuitive. The need to share the experience grows in the moment, and I shoot video and take pictures as if they could somehow capture the profundity digitally. As if I will be able to play back the awe as well as the footage. I’m not sure why, or how, but at this time, in this place, I feel it strongly: This is Important. There is something here. Let’s tell people.

Some things, you can’t learn through research. You must experience them. After years of reading and research, I was actually, finally, standing in a stone chamber. I realized there was much yet to experience and learn about these ancient structures. I would be seeking out more.

Mysterious ancient stone works hide in plain sight across New England: stonewalls, possible perched boulders, stone cairns, effigy works, stone chambers, and more. An author and researcher in Vermont, this year I’ve been exploring stone works — looking more deeply into these ancient stone mysteries of New England. The pandemic detoured me from a planned research trip to Native American mounds and earthworks in the Ohio Valley and beyond. But here at home, I was discovering I might not need to leave New England to experience Native American stone and earth works after all.

It should be noted that there are some who see no mystery in New England’s stones. In 1980, Vermont’s first State Archaeologist, Giovanna Neudorfer wrote in Vermont’s Stone Chambers: An Inquiry Into Their Past, “While there are still many archaeological puzzles in Vermont, the stone chambers are not among them.”

There are many anthropologists and archaeologists who still believe the chambers are simply colonial root cellars, chimney supports or other historic constructions. They attribute all of New England stone works to colonial farmers clearing fields, or building staging for walls, or beautifying their farms to keep their kids from leaving home.

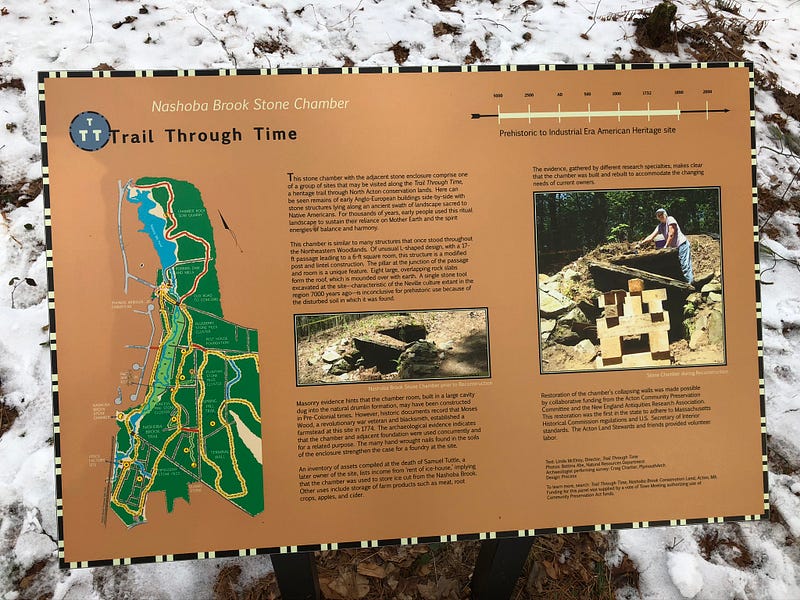

Before visiting the Upton Chamber, I’d trekked in to see another Stone Chamber, on the banks of the Nashoba Brook in Acton, Massachusetts, near a pond in the brook. It’s been studied and stabilized, and tamed for public use — with a plaque out in front and everything.

This first stone chamber I visited gave me no sense of great age, nor did it elicit any visceral response, only a sense of faint echoes of older times, reinforcing the idea these chambers were Colonial and later structures.

Its L-Shaped interior and proximity to the pond, as well as a later land deed from the end of the 19th century describing an “ice house” on the property, all suggest this fairly conventional use for the stone chamber, though it is still an intriguing structure.

Perhaps it predates this usage? I hold out this possibility, though this was not the sense of the archaeologists who restored it, they felt it was Colonial, and this is how they restored it. The problem with restoration is that you restore the structure to what you believe it to have been, as best you can.

And the problem with stone works in New England is that there is a nearly dogmatic belief among mainstream archaeologists that all the stone workings of New England are Colonial. This undermines the field with an unscientific bias, as I alluded to with my guidebook above. This scientism, which leads some archaeologists to disregard results in favor of dogmatic ideas, has roots almost fifty years old.

In the mid to late 1970’s, the mainstream archaeological community found itself pushing back hard against the theories of amateur linguist Dr. Barry Fell and others who proposed the stone chambers and other stone works were built by pre-Columbian European explorers.

This created a circle-the-wagons mentality among archaeologists around the prevailing thought at the time — which itself suffered from a racial bias against Native Americans’ ability to work with stone.

While lecturing the pre-Columbian theorists on their ignorance of 10,000 years of Native American habitation, the archaeologists themselves couldn’t conceive of the possibility that Native Americans had anything to do with the stone works. All were deemed colonial constructs. It was for some reason a given that Native Americans never worked in stone.

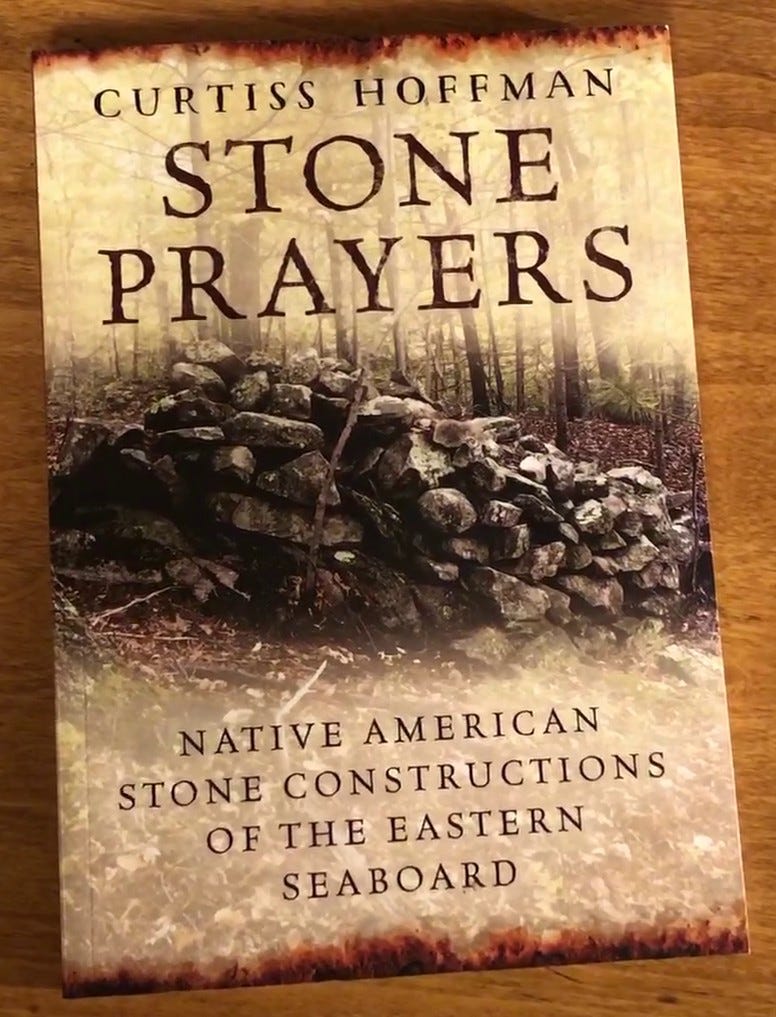

In his 2018 book Stone Prayers, Massachusetts anthropologist and archaeologist Curtiss Hoffman faults many colleagues for indulging in dogmatic scientism for maintaining this attitude today, a view, he said, “Developed without reference to the published literature and as far as I can tell solely based on an aversive reaction to the claims of both nonprofessional and tribal groups…”

In other words? It has no basis in fact. And was born out of backlash. Scientistic. Scientism. But not science.

It is refreshing a professional like Hoffman is actively considering the mysteries of these stone works. Avocational archaeologists — amateurs — researchers like myself, have done most of the legwork up until now.

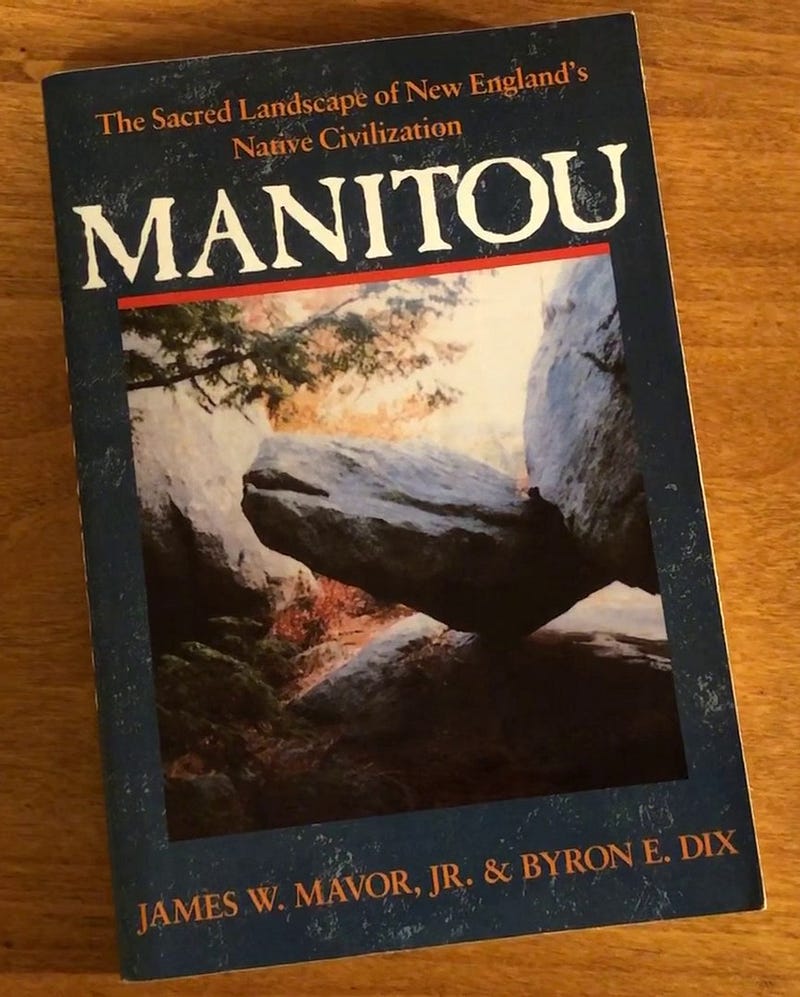

In fact, Hoffman cites two such researchers James W. Mavor Jr. and Byron E. Dix for their groundbreaking 1989 book Manitou, where they proposed that New England stone chambers, walls, and other workings could be of Native American origin, basing their theories on astronomical alignments they found in the stone works. They were the researchers who had found stellar alignments at The Upton Stone Chamber.

Mavor and Dix also spent a lot of time at Calendar One, an area near South Royalton, Vermont. They felt astronomical observations made along ground alignments here allowed Native Americans to mark days and seasons, so they called it a calendar.

The Calendar One Stone Chamber has been missing its roof for a long time. The front left entrance stones are bowed out to the right, creating a bit of a tight squeeze for entry. The right-side interior wall (looking in) has suffered some actual collapse. Yet, it is still an impressive structure. On the beautiful day we hiked into see it, I could sympathize with those such as Dr. Fell who had thought it some sort of ancient temple.

Mavor and Dix’s radiocarbon dating found this chamber to be 435 to 470 years old, possibly built sometime in the 1500s. Their excavation work at this site led them to believe it was likely Native American. The experts disagreed. Nope! Archaeologists insisted this was only a colonial root cellar. The carbon dating was ignored by those who presumed they already had an idea of what the structure was.

I have a hard time believing this to be a root cellar, even now. Granted, the entry stones are bowed in some, but having squeezed in and out, the entryway for this stone chamber strikes me as far too narrow to have been a practical passageway through which to carry in bulk goods. Are they supposed to have passed in the harvest one root at a time?

Nearby Eagle Chamber was said to have been built as a storehouse for apples for cider in late colonial days. But to my eyes, Eagle Chamber’s construction, which incorporates the bedrock, makes it seem an even older construction than the Calendar One chamber, but that is an admittedly subjective idea on my part, and mostly intuitive.

The “official” insistence that both of these stone chambers were constructed in the historic, Colonial period stems more from trying to counter pre-Columbian diffusion exploration speculation than it does deliberately denying Native American agency, but the result is the same.

Now, I’m sure many of these stone chambers were used in colonial times for food or ice storage or whatever — but what about before that? Later colonial usage doesn’t invalidate earlier possible utility, and in fact, later uses might wipe out or obscure any material culture — evidence — of what, if anything, went on before it.

It’s hard for me to tell how old the Calendar Two Chamber near South Woodstock, Vermont is. Mavor and Dix named this stone chamber Calendar Two when they discovered you could see sunrise on the Winter Solstice from the chamber.

When you stop and think about it, it’s a testament to their work and its impact that many of these stone works are still referred to by the names given them by Mavor and Dix.

A rounded mound outside, the inside here is neatly squared off. Its dimensions are said to mirror those of the King’s Chamber of the great pyramid, on a smaller scale. By those who say such things.

Great thanks to my friend, Vermont folklorist and author Joe Citro, for taking me up to see Calendar Two.

Joe also tipped me off to the secret location of a hidden Tunnel Chamber in Vermont. I can’t tell you where it is, but I can show you this unique chamber.

When I heard about this hidden Stone Tunnel Chamber in a secret location, my thoughts went to other ritual tunnels around the world, passages and caves used in rebirth ceremonies and such rites. I learned that this hidden Tunnel Chamber was near water, which suggested to me there could also be a ritual washing element before a climb up through the tunnel to complete a rebirth ritual, as is sometimes found.

The Tunnel Chamber had some huge stones incorporated in its construction, and was built right onto bedrock. It was very clean inside, as if water often washed down through it. The space within narrowed as it rose up the hill, the exit still passable, but it was only human-sized, and hidden somewhat. From a distance, it was extremely difficult to make out the upper entrance, unlike the impressive lower entrance.

Unfortunately, it may look cooler than it actually is. A source of Joe’s at the state’s highway department later suggested the chamber was actually an old stone culvert. Some additional research led me to believe he was right, and that the old road over it was probably washed away in what they call the Great Flood of 1927, around these parts.

From Ancient stones to Highway stones — as you may have noticed, none of these chambers is really the same as any of the others. Each is unique, different in its own way. Seems a mistake to make sweeping generalizations about all of them.

That they may have varied origins makes these stones even more mysterious. The dating that’s been done on some of these chambers and other stone workings certainly suggests they are of pre-historic Native American origin. A picture is emerging of vast Native American Ceremonial Stone Landscapes (CSLs), the land perhaps “tuned” by rows of stacked stones and by perched boulders, the Sacred Landscape acknowledged by participation with it. Or so it seems.

I began my explorations and research into these ancient stone mysteries of New England with an open mind. The more I’ve experienced and learned, the less inclined I am to believe in pre-Columbian European explorers or Phoenicians as the builders of New England’s ancient stone workings. Nor do I think they’re all Colonial.

Instead, I’ve come to believe we are seeing the work of indigenous peoples, the ancestors of our Native Americans of today, and that we have sorely underestimated their abilities, capabilities, aspirations, technology, spirituality — their humanity. In general? We’ve been lied to by our history as to who they truly were.

Cultural erasure, genocide, ethnic cleansing — despite all of these, when we stop and really listen to the stones? They’re still telling their stories. We need to listen better. And keep exploring and experiencing these ancient stone mysteries of New England.