Ancient Astronomical Earthworks of the American Midwest

Celestial Alignments and Embanked Enclosures in Indiana’s Mounds State Park

Celestial Alignments and Embanked Enclosures in Indiana’s Mounds State Park

What little we know about the Adena and Hopewell indigenous cultures of the pre-contact North American Midwest we have gleaned from what remains of their many mounds and earthworks. There is still much to be learned. The earthworks have not usually been valued, however, by post-contact settlers, and so what remains is a tiny fraction of what was once built.

The unassuming earthworks of Mounds State Park in Anderson, Indiana, demonstrate enormous complexity — there is much more to them than first meets the eye. They are some of the best, most intact examples left of these earthworks in east central Indiana. 300 Mounds were once counted in the vicinity. Fewer than a hundred are said to be left in some shape or another — but the two major earthworks here comprise half of those actually intact. Great Mound is said to be one of the best preserved of all of the earthworks in the entire Ohio Valley region.

Archeoastronomy shows these embanked enclosures align with risings and settings of the sun and moon on solstices and equinoxes, and with the movement of the planets, more than 100 of the brightest stars, and star groups like the Pleiades, as well.

This doesn’t actually mean these Native Americans were akin to what we know today as astronomers. Rather, the celestial world was a part of their world. Participating with the patterns of celestial objects may have been seen as honoring them, acknowledging them, and their patterns. And incorporating those celestial objects and patterns into rituals may have tied those rituals into those greater patterns of the universe.

The Anderson Great Mound is a relatively large circular embankment and ditch with a central island. The earthwork is almost 350 feet across, about as long as a football field, and nearly a quarter-mile in circumference.

These days, it’s set off by a wooden fence around its perimeter. A slightly raised boardwalk allows visitors to walk into the center and observe the artificial horizon the embankment creates around the observer inside.

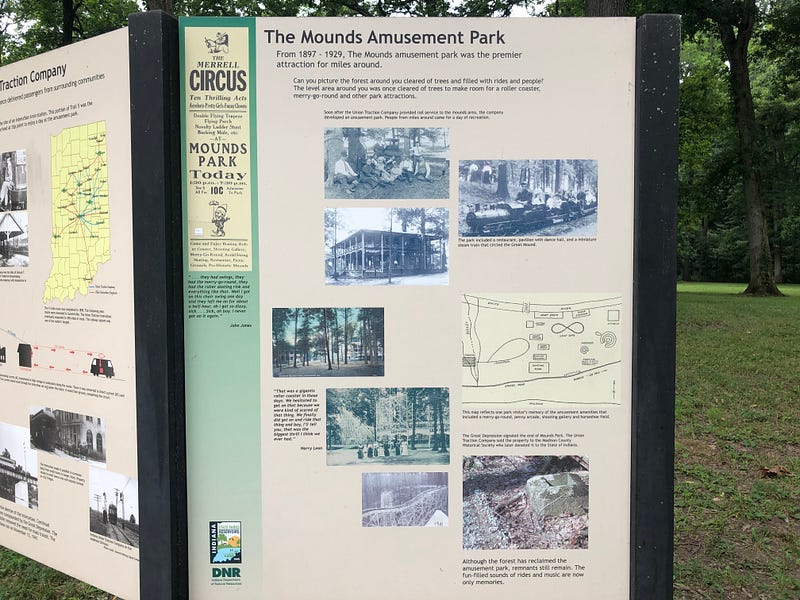

Signage throughout the park details both the area’s ancient and modern history. Kept intact by the Bronnenbergs who farmed here through the 1800’s, the earthwork was preserved into the 20th Century when the land was leased for an amusement park in 1897 — imagine this earthwork surrounded by a roller coaster, miniature trains, a Ferris Wheel and other rides. The Madison County Historical Society later purchased the park and donated it to the state of Indiana, who made it a State Park in 1930.

It was perhaps difficult to track celestial alignments on the heavily forested Indiana plains of 260 BC, and so the earthwork builders were drawn to this relative high ground overlooking the White River to the West.

Fires and cremations were an important part of the rituals that took place at sites like this. The earliest remains here include clay floors and burnt postholes, whose posts were astronomically aligned.

A small mound once covered the middle of the center island. The post holes were found beneath it. The mound was disturbed a few times, looted. It was excavated and removed, long ago.

Carbon dating showed that 100 years after rituals began here, about 160 BC, they began building the embankment and the ditch around the original works. Archaeologists discovered the rim of the circular enclosure followed a deliberate pattern of rises and dips, stomped or pressed into its design.

This pattern was repeated on the other major earthwork here, Circle Mound, and reproduced on a small mound — Fiddleback Mound — next to the Great Mound in a Summer Solstice sunset alignment. The same design.

The embankments’ rims were the visible horizons for those inside the two larger enclosures. Did this design reproduce the horizon of some original homeland? One of ritual significance? The artificial horizons they constructed, though worn down, withstood centuries, still recognizably duplicated on three of these embankments. They were created with definite purpose.

Work began on the other large enclosure here about one AD.

Circle Mound is actually more of a rectangular enclosure. Its longer sides used to bow in, giving it a wide hourglass shape, originally. Its gateways are oriented to the equinoxes’ sunrises and sunset, East and West. There are also solstice alignments here, diagonal through the opposite corners.

A prominent burial was found in the now missing small mound inside of Great Mound which dated back to about the same time as the construction of this newer enclosure. Perhaps the original site was retired along with the prominent individuals, and this new one begun?

We know only a little about the mound building cultures we call the Adena and Hopewell. They were gone from here by about 200 AD, though some inhabitants returned and buried their dead in the mounds a few hundred years later, perhaps in practice of cultural memory.

Still, what we do know has been revealed in places like this, by earthworks like these. Packed with more information than you might think at first glance.

Author’s Note: Much of the information for this piece was provided by The Archaeology of Anderson Mounds, Mounds State Park, Anderson, Indiana (2001) by Donald R. Cochran and Beth K. McCord, available HERE. There were also helpful details on signs in the park and in the pamphlet available on-site. Any speculation is my own. You can find an accompanying video presentation on YouTube.